End of the boom

In 1973 oil costs rocketed by 70% as Arab producer countries belonging to the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) cartel quadrupled their prices. The knock-on effect was a global energy crisis and recession, ending Europe’s boom.

Western European belief in unlimited growth was shattered and traditional industries such as steelmaking and mining went into decline, while new technological and economic sectors emerged. Western countries now had the harsh realities of low growth, inflation and mass unemployment to deal with.

Virtual Tour

The energy crisis directly affected people’s everyday lives, forcing most Western European governments into action. Anti-waste campaigns were organised and Sunday driving bans were implemented to save fuel. The crisis painfully emphasised the degree to which Western economies were dependent on energy imports.

Empty motorways during car-free Sundays

Netherlands, 1973

Rob Mieremet

Photograph

Nationaal Archief, The Hague, Netherlands

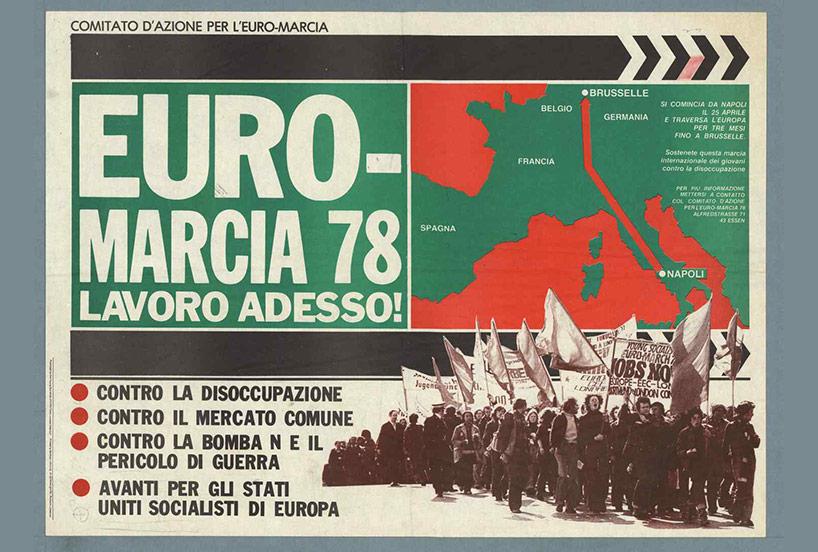

Social cohesion was endangered by the recession, due to rising unemployment, exclusion and alienation. Coordinated action was taken in 1978 when several trade unions organised the first European March against Unemployment, signalling Europeanisation of union struggles and consciousness of transnational interests.

First Euro-March against unemployment

Italy, 1978

Poster, Reproduction

International Institute for Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands

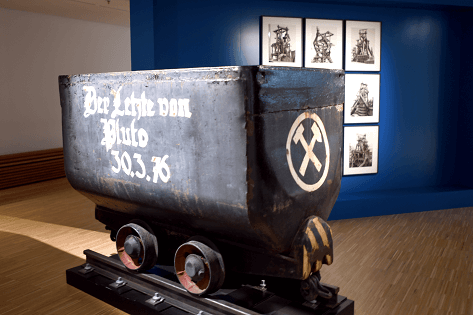

The ‘last coal car’ highlights the decline of long-established heavy industry in capitalist Europe. Once at the forefront of Europe’s post-war boom, such industry was by the 1970s increasingly replaced by the industries of cheaper international competitors such as Taiwan, South Korea or Brazil. European countries turned to nuclear energy in order to become less dependent on foreign oil.

Last coal car

West Germany, 1976

Steel

Westfälisches Landesmuseum für Industriekultur, Bochum, Germany

Democratisation in western Europe

Inspired by the student 'revolutions' of the late 1960s, a new generation wanted change and were prepared to fight for it. Tired of the old attitudes and ways of doing things that had been in place for decades, they now demanded more individual rights and opportunities to participate in politics.

Greece, Spain and Portugal all saw their ruling dictatorships collapse between 1974-1975. Although the events were different in each country all three experienced political instability, economic crisis and painful historical legacies on their paths to democracy. They would eventually enter the fold of the European Community.

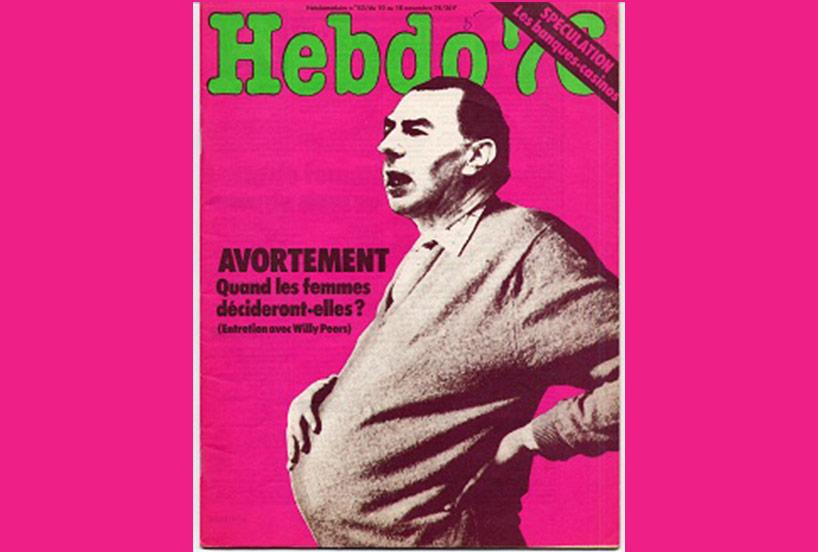

Women increasingly shone a spotlight on continuing inequality between the sexes throughout the 1970s. While most had the right to vote, they still experienced discrimination and restricted freedoms in public and private life. Feminism emerged as an active force that hoped to end patriarchal domination and create truly equal societies.

"Abortion. When will women decide?"

Belgium, 1976

Magazine cover, Reproduction

Institut d'Histoire Ouvrière, Economique et Sociale, Seraing, Belgium

In 1974 a military coup ousted Portugal’s ruling dictatorship. Army officers keen to introduce democratic and economic reform and begin decolonisation were eventually supported by the Portuguese public. Termed the ‘Carnation Revolution’ due to the flowers placed in soldier’s weaponry, the mainly peaceful events put the country on the road to democracy.

"Carnation Revolution"

Lisbon, Portugal, 25 April 1974

Eduardo Gageiro

Photograph, Reproduction

New social movements emerged, with Western Europeans taking to the streets to march under banners supporting gender and LGBT rights equality, environmental issues and peace campaigns. These voices seriously questioned how and whether parliamentary democracy could meet their needs.

Anti-nuclear badges

Europe, 1970-1985

Amsab-Institute of Social History, Ghent, Belgium

Communism under pressure

The contradictions between communist propaganda and the realities of people’s daily lives became increasingly obvious in the 1970s and 1980s. Economic stagnation replaced former rapid growth, and debt crippled countries.

By the end of the 1980s, food shortages, constant surveillance, censorship, restrictions and even prohibitions on travel outside the communist bloc were causing frustrations and tensions, in some cases to an unbearable degree, among citizens of these countries. Such frustrations would all play their part in the eventual fall of communism in 1989.

Virtual Tour

The communist leader of Romania, Nicolae Ceausescu described his rule as a ‘golden age’. The cult of personality that he and his officials created around him was perhaps one of the most outlandish of all communist regimes. Under Ceausescu the Romanian people suffered some of the worst deprivations and repression of Eastern bloc countries.

"The Hero of Peace" (Nicolae Ceausescu)

Romania, 1965-1989

Deak Barna, Painting, Reproduction

Muzeul National de Arta Contemporana / National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest, Romania

The 1980s saw increased Polish opposition to communist rule, building on previous workers' unrest starting in the 1950s. Striking workers at the Gdańsk shipyard established a free trade union called Solidarność, demanding better life conditions and political reforms.

Collecting box. Support for Solidarność

Sweden, 1980-1989

Ośrodek Karta, Warsaw, Poland

In a few short months in 1989, the people of Central and Eastern Europe give a decisive push to the communist regimes that had controlled them for decades. They fall one by one like dominoes and the Iron Curtain, symbol of a divided continent, disappears.

Pole with barbed wire

Austrian-Hungarian border, 1940s-1950s

Wood, metal wire

Haus der Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, Germany

Milestones of European integration II

A thawing of relations took place between the Western and Eastern blocs. In 1975, thirty-five countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union, met in Helsinki, Finland, for the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

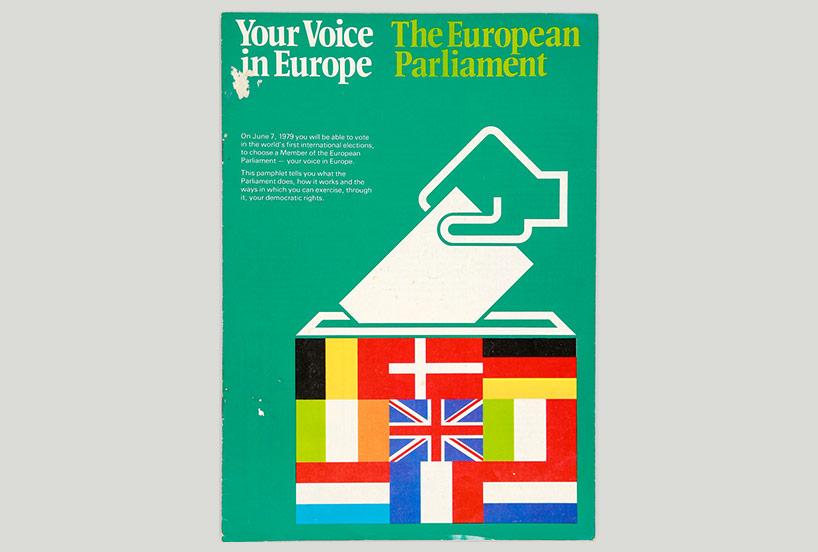

1979 – a historic occasion for increased democracy in Europe, with the first direct elections to the European Parliament by citizens of the Member States. No longer would this important assembly be selected by national parliaments; it was now the first international body directly elected by universal suffrage.

What is the Single Market? It’s the creation of a unified economic area where people, money, goods and services can move freely. The European Single Market had been one of the European Community’s main goals from its foundation.

This is the signature of Aldo Moro, Prime Minister of Italy and President of the Council of the European Community, on the Helsinki Declaration. For the first time ever, the conference had given the European Community the chance to speak with ‘one voice’ as a major diplomatic player on the world stage.

Ink-blotter for Helsinki, Final Act

Finland, 1975

Silver

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

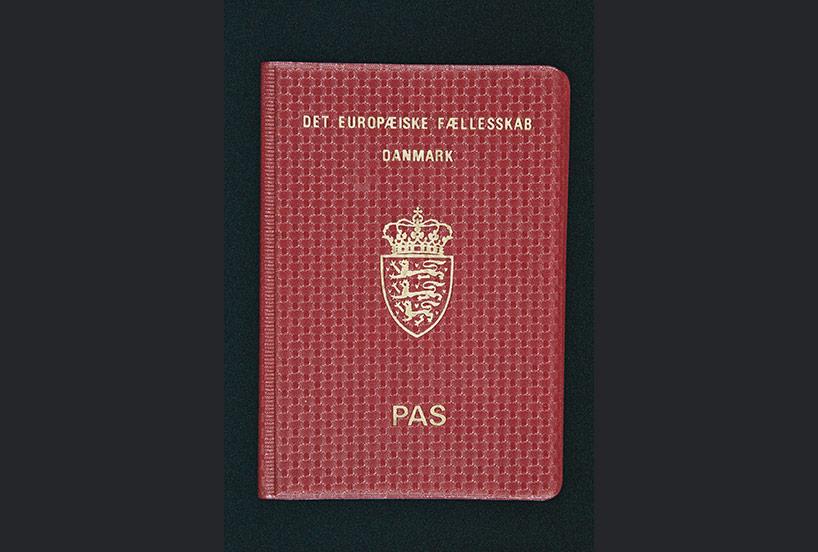

The European passport introduced in 1985 highlights the new possibilities of free movement and symbolises concrete efforts of the European Community to create a sense of European citizenship.

EC/Denmark passport

Denmark, 1994

Private collection, Brussels, Belgium

1979 – a historic occasion for increased democracy in Europe, with the first direct elections to the European Parliament by citizens of the Member States. No longer would this important assembly be selected by national parliaments; it was now the first international body directly elected by universal suffrage.

Leaflet for the European elections

United Kingdom, 1979

Reproduction

Personal collection, Brussels, Belgium

Re-mapping Europe

The map of Europe was transformed again after 1989 with new nations emerging and old borders re-drawn.

A re-united Germany came peacefully into being in 1990 under international supervision. The same could not be said however for the former Yugoslavia where ethnic, religious and cultural differences led to brutal civil wars and ethnic cleansing.

Virtual Tour

Slovenian and Croatian declarations of independence led to armed conflict that then spread to Bosnia-Herzegovina, where ethnic groups clashed. Genocide and ethnic cleansing became horrific trademarks of a war that ended in 1995 with the Dayton Peace Accords. Serbia’s President Milosevic and military leadership would again utilise ethnic cleansing in Kosovo

Funeral in Kosovo

Yugoslavia, 1990

George Merillon

Photograph

World Press Photo

Amsterdam, Netherlands

On the 3rd October 1990 Germany once again became a unified country. The momentum for reunification was increased by a continuing exodus of people from East to West following the fall of the Berlin Wall and election results in Eastern Germany of that year showing that citizens wanted it. The reunification treaty was agreed with the post-war occupying nations, the USA, Soviet Union, France and Great Britain.

Reunification celebration at Brandenburg gate

Gilles Leimdorfer

Berlin, Germany, 3 October 1990

Photograph

AFP/Getty Images

Milestones III

Whether they like it or not, Europeans' modes of living are increasingly similar even if their diverse cultural identities remain vibrant... Open borders, increased mobility, better communications, shared laws and a single currency are all having an effect. You could call it ‘Europeanisation’.

The European Union is now more politically united than it has ever been, but internally still very diverse. What will the future bring? Will Europe continue to integrate? Or will it fragment again? Will its original beliefs – in peace and the four freedoms – survive the test of time?

A number of politicians, civil society groups and businesses had been calling for the creation of a common currency for years. As far back as 1969, European leaders had considered an economic and monetary union, and the 1960s and 1970s saw public demonstrations in favour of such an initiative.

Mock Euro coin

Italy, 1965

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Over the course of the second half of the 20th century Europe turned from a continent of emigration to one of immigration. As legal immigration was restricted, illegal immigration increased from the 1980s. Objects spilled back to the Tunisian coast area are a tragic symbol of their plight.

Baby shoe protected from water

Zarzis, Tunisia

Collected by Lihidheb Mohsen

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Successive economic bailouts, tax payer liability and controversial national austerity measures became a litmus test of citizen’s allegiance to the EU project. Euroscepticism and anti-EU sentiments increased; nationalist and extreme right-wing tendencies flourished with the EU flag burnt in several countries such as Greece, Hungary and Spain.

Flag “No” for the Greek bailout referendum

Greece, 5 July 2015

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

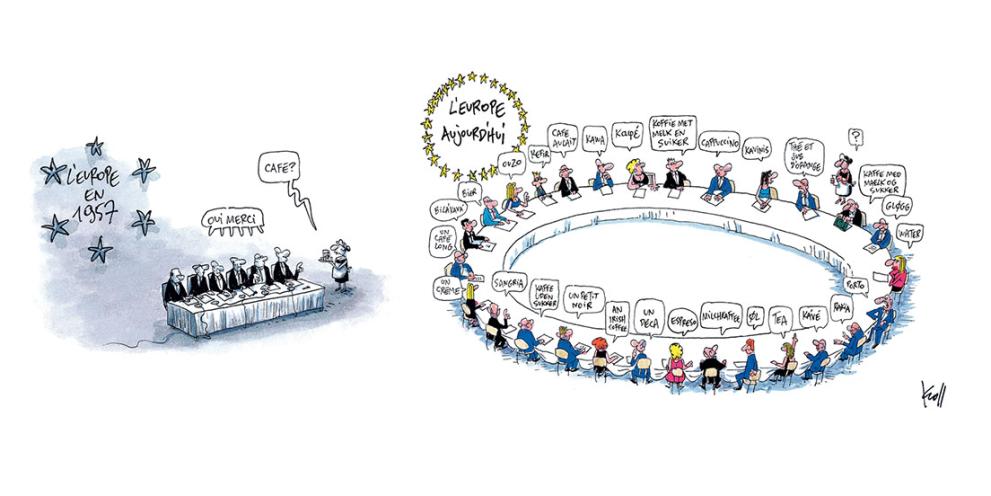

The number of Member States more than doubled following the end of the Cold War. Sweden, Finland and Austria joined in 1995, followed by 10 countries in 2004. Romania and Bulgaria joined in 2007, and Croatia in 2013.

Europe: 1957 versus 2007

Brussels, Belgium, 2007

Pierre Kroll Cartoon

Reproduction

Pierre Kroll collection, Liège, Belgium

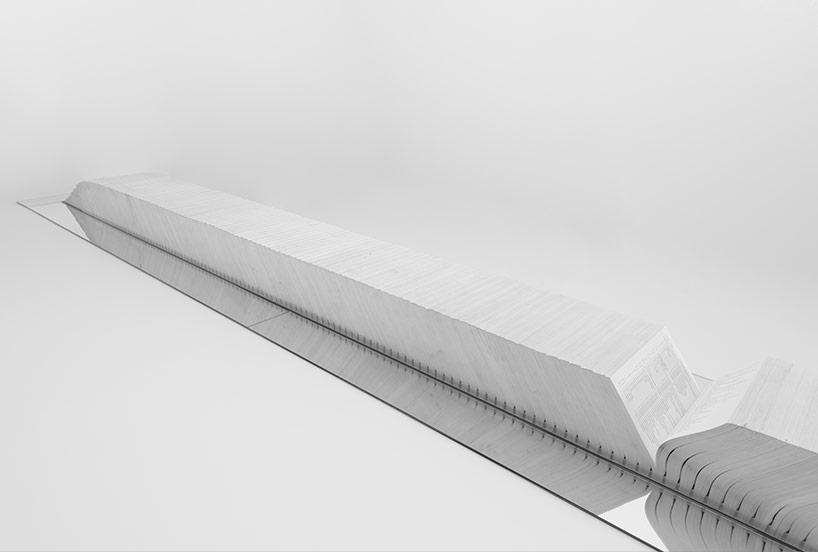

What is Europeanisation? It’s the acceptance and implementation of common laws by all EU Member States, fostering an increasing convergence of interests and growing similarities. These laws, known as the acquis communautaire, were developed over several decades, and countries joining the EU must integrate them into their national legal systems.

80000 pages of EU law

Netherlands, 2003

Rem Koolhaas

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Virtual Tour

After 1989 people no longer accepted the communist view of history, which promoted the Soviet Union and the Red Army as the liberators of Central and Eastern Europe from the Nazis. For many, the Soviet intervention was simply another occupation. Communist statues and street signs became subject of public debate, were removed or even destroyed.

Relief of the monument to the Soviet Army painted with pop-culture characters and later cleaned

Sofia, Bulgaria, 2011

Reproduction

Thomson Reuters Corporation, New York, United States

Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015 Reproduction

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

This euro coin shows the Slovene Franc Rozman, a communist who fought bravely against the Nazi occupation of his country. The red star on his chest – a symbol of communism – appears alongside the EU stars.

Euro coin acknowledging communist partisan

Slovenia, 2011 Metal

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

The opening up of former secret files and archives in post-communist countries was vital in enabling people to come to terms with the communist past. The true extent of state spying and repression came flooding out.

Dollop made from Stasi files

Leipzig, East Germany, 1989

Paper Bürgerkomitee Leipzig e.V., Träger der Gedenkstätte

Museum in der Runden Ecke mit dem Museum im Stasi-Bunker, Leipzig, Germany