Europe and the Thirty Years’ War

27 April 2024 - 12 January 2025

Free admission. No advance booking required for individuals or groups under 10 persons.

Guided tours

Guided tours of the Bellum et Artes exhibition are available for general audiences in English, French, Dutch and German. The tours focus on assessing the Thirty Years' War through the lens of different kinds of art, using an "active participation" method, based on Visible Thinking Routines.

- Duration: 60 minutes

- Group size: 10 - 15 persons

- Booking time: one month in advance

Overview

The international exhibition centres on the role of arts during the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). Named Bellum et Artes (War and Art), the exhibition unravels the complex interplay between conflict and artistic expression.

Bellum et Artes explores an early large-scale conflict in Europe through the warring parties’ strategic employment of the arts as a military propaganda tool and to accentuate their power. It goes on to demonstrate the impact of works of art as ‘ambassadors of peace’. The migration of artists and the displacement of artistic treasures during this period are subjects which can be analysed through interactive media stations. Furthermore, Bellum et Artes delves into the struggle for peace, illuminating political schemes and the genesis of legal and political principles that continue to have relevance today.

Running until early 2025, the exhibition is accompanied by events on the theme of “War and Art” — such as guided tours and film screenings — enriching visitors’ understanding of the first pan- European war and the significance of this subject matter for our times.

Bellum et Artes is a Europe-wide research project involving a dozen institutions from seven countries, coordinated by the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe and the Dresden State Art Collections. The exhibition in Brussels has been co-curated with the House of European History team and highlights the main results and findings of this international collaboration.

The Exhibition

The conflicts during the Thirty Years’ War had a profound impact on Europe, scarring the continent. The Bohemian Revolt of 1618 sparked a prolonged war until 1648, intertwining various battles — fuelled by power struggles, religious tensions and claims of supremacy — with political landscapes across the regions.

Partner interviews

We asked curators, partners and contributors to Bellum et Artes at the House of European History, to discuss one key object from the exhibition.

The actors of war and the role of art

European ruling houses, linked through intricate family ties, leveraged political and religious alliances to assert inheritance claims. In addition to wielding weapons, these dynasties engaged in artistic diplomacy, using valuable artworks as symbols of power and diplomatic gestures. Despite being in wartime, substantial investments were made in art, highlighting the role of targeted image campaigns to enhance prestige and support for European royal courts. The actors in the war were the leading dynasties ruling European states, such as Spain, France, Denmark and Sweden, and represented the most powerful houses in the Holy Roman Empire.

Johannes Wundes the Younger (active circa 1590–circa 1630) (rapier), Clemens Einhorn (dagger)

Ornamental weapons set of Elector John George I of Saxony

Rapier and dagger, German, before 1640. Rüstkammer, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany

How does war work?

When waging a war, princes and states assigned its organisation to private military enterprises. These were experts in the military and made a business out of war, enlisting mercenaries and leading the campaign. However, equipping and sustaining an army was extremely costly, so extorting contributions was inevitable, though put a heavy burden on the population. Many troops were ill-disciplined and plundered villages and cities, disregarding orders and martial law.

War chest; armoured and suitable for use in the field with a sophisticated locking mechanism

Rüstkammer, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany. Photo: Thomas Seidel

The horrors of war

The Thirty Years’ War came with unparalleled loss of life and devastation, thus establishing a traumatic period in European history. Approximately one-third of the Holy Roman Empire’s population succumbed to violence, starvation, and disease. Civilian suffering was exacerbated by violent attacks, rapes, and lootings by both opposing and allied troops. Artists, drawing from their own war experiences, depicted these atrocities in their works, deliberately contrasting the horror with aesthetic appeal, which has resonated with contemporary collectors.

Daniel Hubatka, former soldier, Documentation of war injuries, 1655

Sächsisches Staatsarchiv - Hauptstaatsarchiv Dresden

War in the media

The war, perceived as a European event, sparked a media boom with widespread circulation of printed news, including broadsheets and pamphlets. Both sides used these materials for propaganda, turning the media into a secondary battlefield for sharp satire and the dissemination of ‘fake news’.

Simon van de Passe (?) ‘The Great European War Ballet’

Northern Netherlands, 1632. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Art and artists during the war

During the war, cultural goods became especially endangered objects. Royal rulers were aware of the importance of art treasures. Among others, lootings took place in the conquests of Heidelberg (1622), Mantua (1630), Mainz (1631), Munich (1632), Stuttgart (1634/35) and finally Prague (1648). The victors took ownership of artworks and books, adding them to their own collections or gifting them in exchange for favours. Given its background and eventful history, looted art from that period can be considered a significant part of Europe’s common cultural heritage.

Domenico Fetti (1589–1623), David with the head of Goliath, 1614/1615

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister photo: Elke Estel, Hans-Peter Klut

The road to peace

Efforts for peace after the 1618 conflict initially faltered until the 1648 Peace of Westphalia. Legal experts had laid the foundations for modern international law, limiting the right to wage war to sovereign states. Diplomats, as legal experts, played key roles in shaping peace negotiations. The Peace of Westphalia reorganised the Holy Roman Empire and granted sovereignty to the Netherlands and Switzerland. Despite peace in Europe remaining elusive, the peacemaking objectives persisted. The Nuremberg Implementation Congress in 1649-1650 consolidated the initially fragile peace by ensuring the demobilisation of troops, resulting in a celebratory festival marking the war’s end.

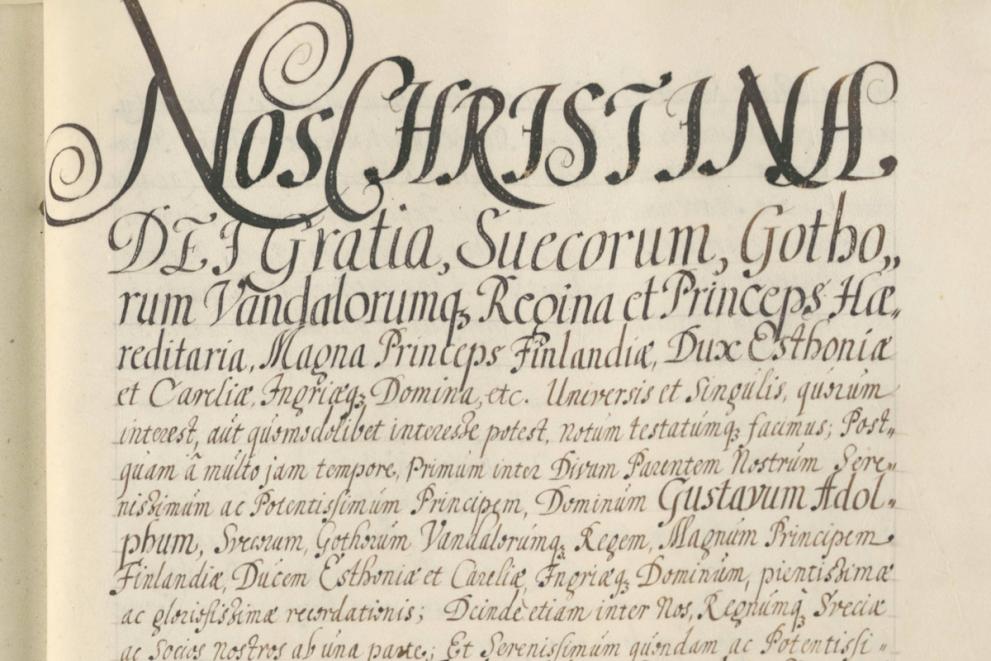

Ratification of the Peace Treaty of Osnabrück by Queen Christina of Sweden, Stockholm, 18 November 1648

Sächsisches Staatsarchiv – Hauptstaatsarchiv, Dresden, Germany

Europe after 1648: war and peace

Despite the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Europe did not achieve lasting peace. Wars, militarisation, and colonial expansion continued, leading to devastating conflicts. Efforts for universal peace through initiatives such as the Hague Conventions and the League of Nations were undermined by the two World Wars. While the European Union has prevented member states from waging war against each other since World War II, the threat of conflict persists in Europe, whilst continually being condemned as a means of achieving political goals.

Martin John Callanan (born 1982), Wars during my lifetime, 2014, video, 14'.20", Courtesy of the artist

Partner institutions