Political change

The 19th century – an age of revolutions! Taking inspiration from the French Revolution of 1789, people across Europe challenged aristocratic ruling classes and fought for the development of civil and human rights, democracy and national independence.

Nationalism emerged as a revolutionary claim promising citizens more involvement in democracy, but it was exclusive, imagining a world of national territories inhabited by ethnically similar people. Some visionary Europeans, however, hoped for the unity of the continent beyond national allegiances.

Virtual Tour

The revolutionaries across Europe challenged aristocratic privileges and traditional orders. In particular, the revolutions of 1848-1849 were a milestone in the fight for equality, self-determination and human rights, goals which have strong echoes for our own times.

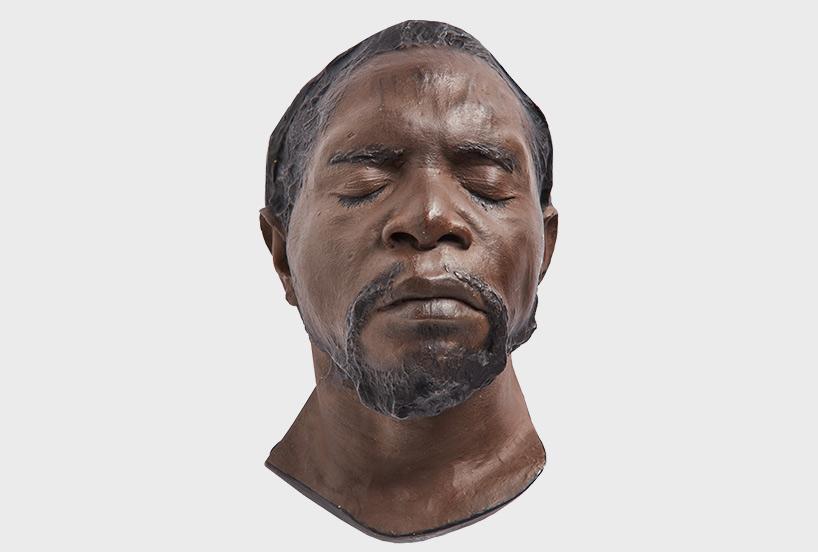

“Erection of Barricades”

German Confederation, about 1850

Construction toy Wood, paper

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

The French Revolution of 1789 was a turning point in European history. Existing political systems were undermined as the ideals of ‘freedom, equality and fraternity’ swept across the continent. The French revolutionaries’ attack on the Bastille prison in Paris on 14 July 1789 has become a famous symbol of resistance to corrupt rule and aristocratic privilege.

“Siege de la Bastille” (Storming of Bastille)

Paris, France, 1970, after Jean-Bertrand Andrieu (1761-1822)

Enlarged medal in cast bronze

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Legends, myths and a glorious past all became important elements for national movements trying to forge a national identity – an identity that was imagined as separate and unique from others. Flags, anthems and symbols were just some of the devices used by national movements to achieve these goals and enhance their self-image.

Legendary oath of the Swiss Confederacy

Switzerland, 19th century

Ceramic plate

Swiss National Museum, Zurich, Switzerland

Markets and people

Steam, smoke, factories, noise – all announced the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain. To different degrees manufacturing then spread across Europe turning the continent into the world centre of industrialisation, finance and commerce. New technical innovations initiated industrial progress with steam power driving the development of heavy industry. Methods of production were totally transformed and large factories with thousands of workers mass produced industrial and consumer goods.

Workers in the 19th century were wage labourers who did not have legal protection or social security. They often had to work and live in appalling conditions. Only at the end of the century did their situation improve with the gradual attainment of voting rights.

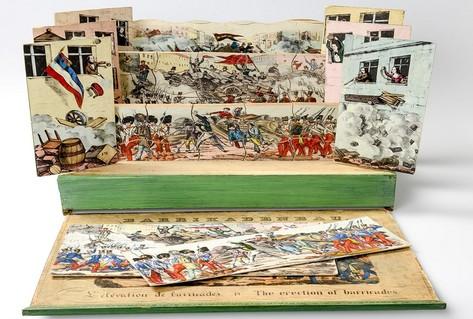

Advert for Maison du Peuple

Brussels, Belgium, 1899

Poster Reproduction

Amsab-Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis, Ghent, Belgium

Industrialisation and the introduction of mechanised manufacturing utterly changed working conditions for people across Europe.

Nasmyth steam hammer

Great Britain, ca. 1850

Replica

Science Museum, London, United Kingdom

Originating from the French language, the word bourgeoisie describes a new social category of people who emerged out of the changes in society brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Economically independent, educated and gaining political rights, they were the driving force behind economic and political changes.

"Portrait de Monsieur et Madame Georges Hobé"

Belgium, 2nd half of the 19th century

Gustave Vanaise (1854-1902)

Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts / Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten, Brussels, Belgium

Science and technology

Speed, dynamism and a belief in progress defined Europe at the end of the 19th century. Railways, electricity, cinema, photography and new theories in science and medicine affirmed Europe’s leading role in this technological coming of age. A time of optimism beckoned.

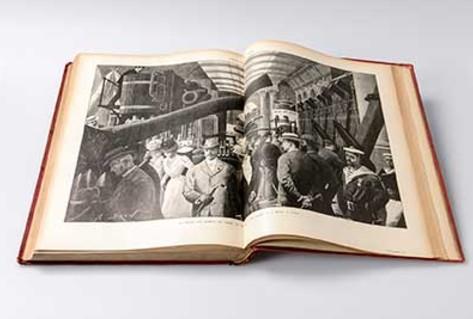

The arrival of the age of railways demonstrated Europe’s advance as an assured technological world leader. Industrialisation expanded and long-distance travel became possible across all social classes.

Railways altered European landscapes with the introduction of tunnels, viaducts and bridges over previously impassable obstacles. What was then the longest tunnel in the world opened in 1882 with the completion of the 15-kilometre Gotthard rail tunnel connecting northern and southern Europe. Railways brought mass transit and tourism.

Northern Europe to Italy via Gotthard railway

Lugano, Italy, 1898

Artist Unknown

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

The telegraph allowed almost instant communication between distant places. A crime committed in one city could be rapidly reported in another, as could world commodity prices. Undersea cables made communication global.

Early telegraph used in Belgium

London, Great Britain, ca. 1844

Cooke and Wheatstone

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Late 19th century national rivalries and international tensions were obvious within the Universal Exhibition of 1900, with galleries displaying weapons of war and colonial villages. Such rivalry would dramatically shape the following century.

Weapons of war

Universal Exhibition Paris, France, 1900

Exhibition Catalogue

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Imperialism

The 19th century witnessed a globally dominant Europe. Empires expanded, colonies amassed – all pushed energetically forward by the Industrial Revolution. Colonies provided the raw materials and luxury commodities to meet rising consumer demand, in return promising vast markets for European products. Abuse and inequality were excused as a necessary part of ‘civilising’ savage peoples. The gradual ending of slavery was followed by new forms of intolerance and racism.

By 1914 European countries ruled about 30 % of the world’s population. Europe had been involved in overseas exploration and trade for centuries, but the benefits of the Industrial Revolution enabled Europe to tighten its grip on other continents.

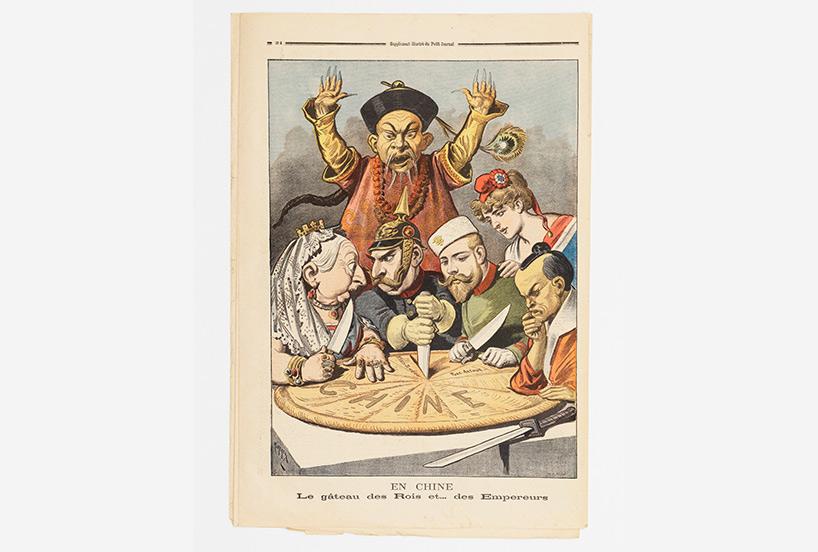

The participants at the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) established the ground rules for partitioning the continent of Africa among European powers, without any input from Africans themselves. By the end of 1900 only three states remained independent. European powers would also divide up the map of Asia.

Europe and Japan carve up China

Le Petit Journal, Paris, France, 1899

Henri Meyer (1844-1899)

Cartoon

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

New European technology created tools, such as machine guns, that were decisive in advancing colonialism. Even with superior numbers, indigenous resistance was futile against a weapon that could fire 50 times faster than a standard rifle.

Rapid fire Maxim machine gun

Hiram Maxim, (Inventor) 1840-1916

United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, late 19th century

Royal Armouries of the United Kingdom, Leeds, United Kingdom

Within Europe itself, certain peoples were regarded as being racially ‘less evolved’ than others. According to such racist concepts, these societies were usually described as being on the geographical and social margins of Europe and were often seen as the living ancestors of 19th‑century Europe’s more highly developed races.

Cast of a Zulu boy

Berlin, German Empire, 1891

Castan’s Panopticon

Plaster

Ard-Mhúsaem na hÉireann, Dublin, Ireland