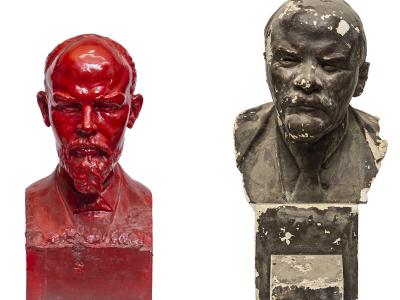

Lenin facing Lenin

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- Cca. 1950s-1960s

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1990

- Place of origin

- Unknown

- Current location

- National Museum of the Romanian Peasant, Bucharest, Romania

Personality cult, kitsch and oblivion: Busts from the Lenin-Stalin Museum, which existed in Bucharest.

The two busts form part of the V.I. Lenin personality cult, which began in the USSR and spread across the entire Eastern bloc following the installation of socialist state regimes. They bear witness to the way in which museums handle artefacts over time. They come from the Lenin-Stalin Museum established in 1951-1955 in Bucharest (as a branch of the Central V.I. Lenin Museum in Moscow), which operated in various guises until 1990. The busts most probably arrived from the USSR in the 1950s, although after 1945 such sculptures were also produced locally. The history of the Soviet-inspired museum is currently being researched.

The two busts mirror the relations between Romania and the Eastern bloc as a whole, including the USSR, which became the hegemonic power in Central and Eastern Europe after 1945. The Central V.I. Lenin Museum in Moscow also had branches in several Eastern bloc countries, each broadly replicating the example given by the central museum. The destruction of statues of communist leaders in the 1989 anti-communist revolutions across the entire Eastern bloc is part of the history of de-deification of the leading figures of communism – from the demolition of their statues to their revaluing in places like Grūtas Park or Memento Park – of which these busts form part.

In 1990, the newly established Museum of the Romanian Peasant inherited the building and a large part of the Communist Party museum’s collections, which it either gave away or threw away. It later found that the basement was home to an additional storeroom where, in the second half of the 1960s, the artefacts from the former Soviet museum had been moved. The two busts most probably come from among that museum's exhibits and were ‘hidden’ in that storeroom when – still in the communist era – Romania distanced itself from the Soviet hegemony and took a nationalist cultural and ideological direction. Thus, the iconic figures of Soviet communism were replaced with a new, national mythology in which the Romanian Communist Party and the state become intertwined.

There are multiple associations between the artefacts and waste. Firstly, both busts were disowned after the Bucharest regime took a nationalist direction. Furthermore, after 1990, all the artefacts of the newly established Museum of the Romanian Peasant started to be classified into art-related aesthetic categories. The busts therefore underwent a double-downgrading: as reproductions of an original and as belonging to the Socialist realism art form. The red bust was exhibited at the "Ciuma" ("Plague") exhibition, and removed from the world of mass production by being modified and implicitly turned into kitsch, which itself is associated with the manipulation of emotions. It was then forgotten, along with the grey bust.

Material

Plaster, toning/varnish

Dimension

61 x 34 x 32 cm (Grey Lenin); 52 x 24 x 21 cm (Red Lenin)

Inventory number

C.Sc-0001, C.Sc-0002

Status

In storage

Image credit

Copyright NMRP

Brick from the demolished Rakusch Mill

- Artist / Maker

- The public trading company First City Mill (Erste Stadtmühle Josef Lenko & Comp.)

- Date production / Creation

- 1903

- Entry in the museum collection

- 2014

- Place of origin

- Celje, Slovenia, Europe

- Current location

- Museum of Recent History Celje, Celje, Slovenia

If the walls could talk… What stories can be told by a worthless old brick?

The brick is from the demolished Rakusch Mill building. This was the first mill in Celje, where cereals were milled using steam power. The mill was built in 1903 and operated until 1935. After it shut down, the building was used to store heavy iron for the Rakusch trading company. The imposing brick structure of the Rakusch Mill was one of the most recognisable buildings in Celje. For over a century it stood as a gateway to the city. From 2002 the abandoned mill was protected as a monument of local importance, but a fire that engulfed the building in 2014 sealed its fate.

Rakusch Mill stood next to the railway line, which meant the owners could bring in low-price grain from other parts of Yugoslavia and so keep down the price of flour. The mill was part of the Rakusch wholesale trading company, which already at the time of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the biggest such companies in this part of Europe, doing business in seven languages. During the time of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, it shifted its business focus to the Balkans.

In the eyes of the townspeople, the Rakusch Mill has undergone many changes over the years, from being a symbol of industrial pride at its peak to the abandoned and neglected building it had become in recent decades. In November 2014, the derelict building caught fire. It was so seriously damaged that the municipality of Celje decided not to restore it but instead demolished it that same year. With the help of Slovenia’s Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, some of the brickwork was retrieved by the Museum of Recent History Celje to be preserved for future generations as a potent symbol.

The Rakusch Mill was a cultural monument of local importance, but after the building was devastated by fire the remains held no value. The brick which the Museum of Recent History Celje keeps in its collection could easily have ended up in a rubbish dump along with the rest of the ruins of the mill. Instead, as part of a museum collection its value is preserved as a piece of cultural heritage. Its power lies not only in its historical value as an integral part of one of the most important industrial buildings in Celje, but also in the way it bears witness to the cultural heritage and the fate of a cultural monument which ended up as scrap as a result of inadequate maintenance.

Material

Fired clay

Dimension

60x135x265 mm

Inventory number

745:CEL;S-23489

Copyright

Celje Museum of Recent History

Status

In storage

Image credit

Matic Javornik

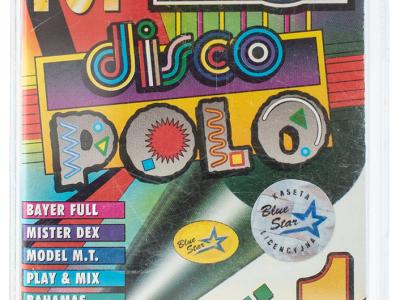

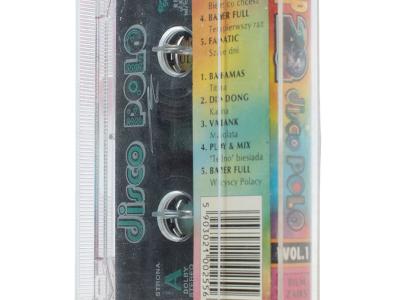

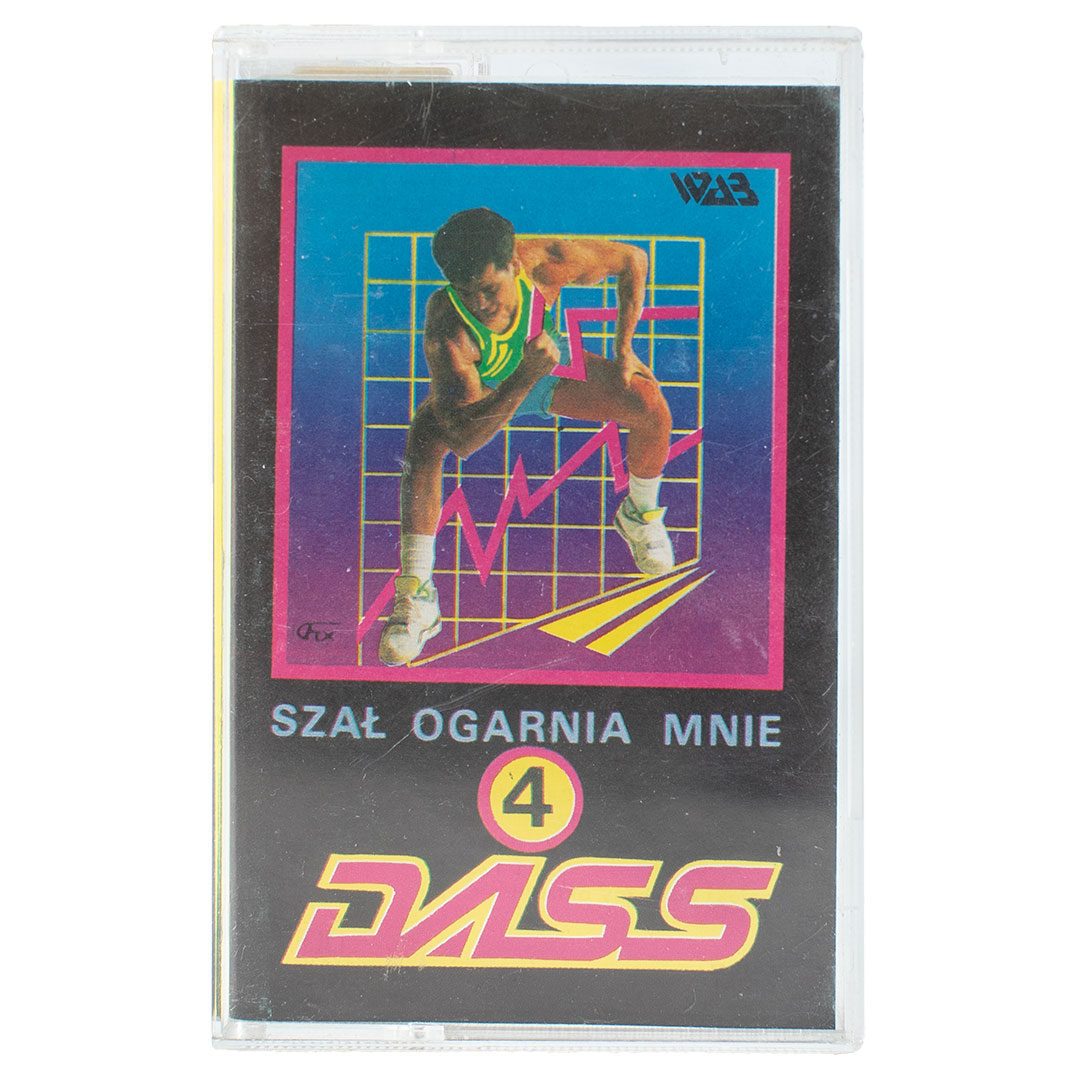

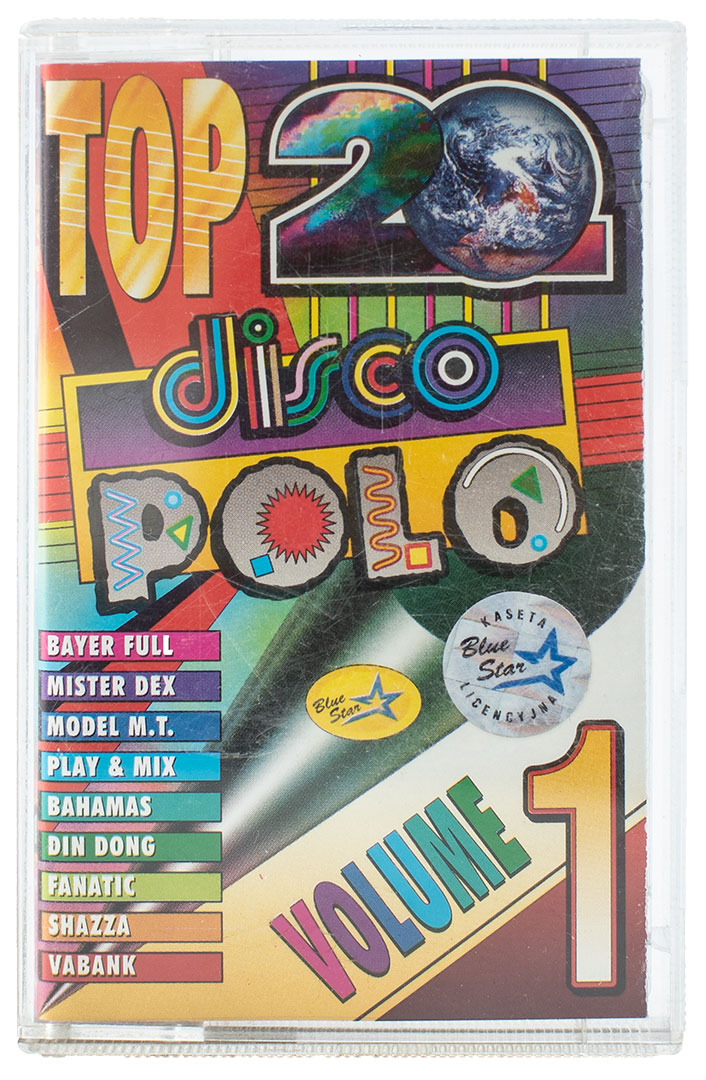

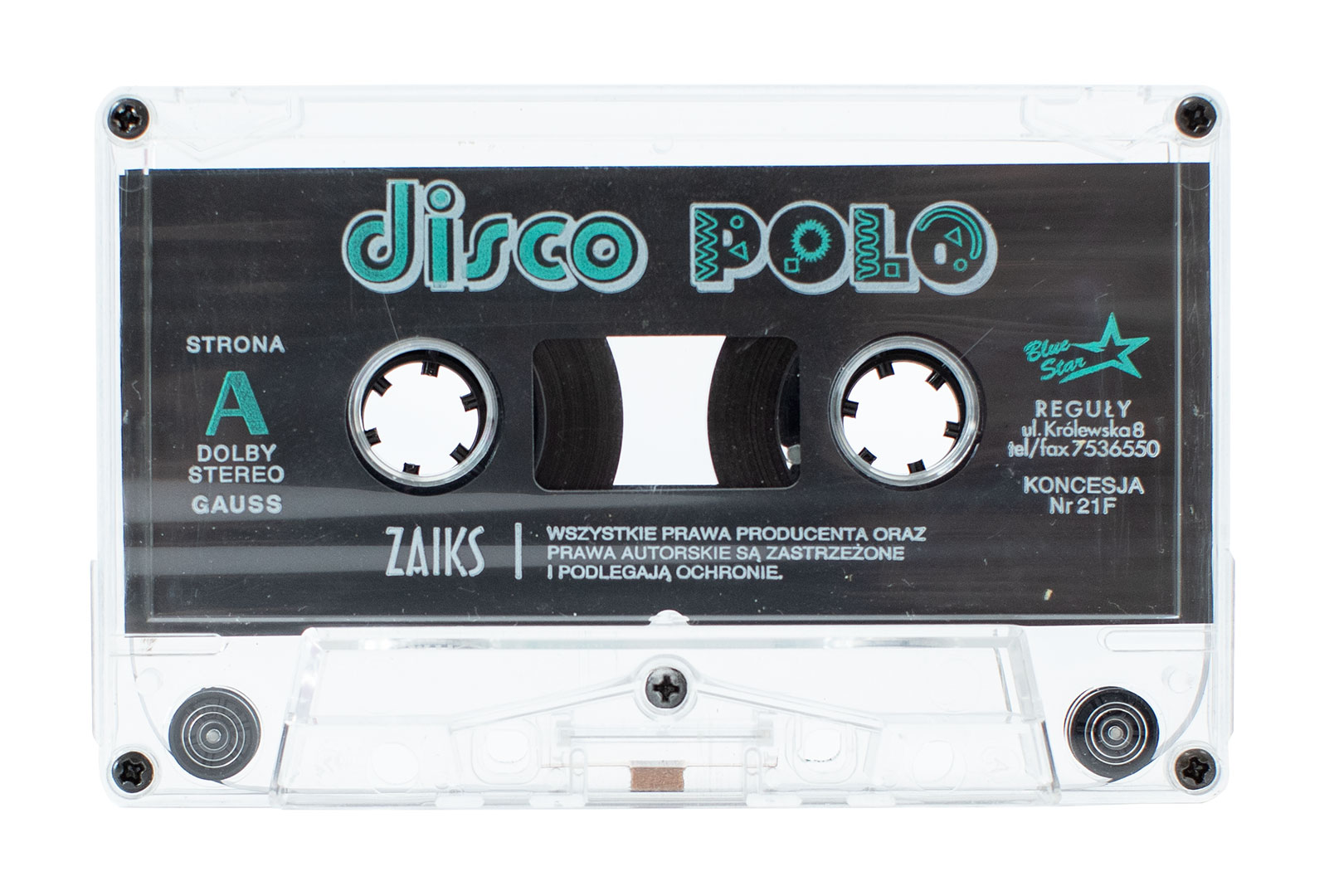

Trash Music?

- Artist / Maker

- Dass, Shazza, Top 20 Disco Polo

- Date production / Creation

- Record label WAB/after 1991, Blue Star/1996, 1994

- Entry in the museum collection

- Outside collection, educational collection

- Place of origin

- Janów Podlaski, Lubelskie Province, Poland, Europe

- Current location

- National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Critics are often quick to dismiss pop culture as garbage. What can we salvage by picking through their rejects?

The mass Disco Polo phenomenon grew out of the subsoil of Poland's post-1989 political and economic transformation. It was a reaction by a section of society to the incomprehensible debate about the possibilities of a capitalist economy, while also being one of the first expressions of capitalist audacity. Disco Polo production companies were among the first private initiatives on the music market, and the lack of control present at the time created opportunities for many abuses in the form of, for example, musical piracy. As a musical trend, aesthetically and lyrically, it presented Poles' ideas of the world we longed for: motorways, the West, exotic countries, eroticism. In the opinion of critics of the time, it was a musically and lyrically worthless product for the masses. As a cultural practice – present at feasts, weddings and fire station parties – it was seen as an expression of the bad taste of the lower classes of Polish society. Finding it of little value, they pushed it to the margins of culture, despite its widespread presence, thus building a social divide.

Disco Polo, like any product of contemporary culture, operates at the intersection of two spheres – the economic and the cultural – and as such can end up being relegated to the dustbin. It is not linked to specific places, but to social situations. It creates groups of participants who, for a brief moment, become a community constituted around having fun. As a result of the confrontation of different cultural models, Disco Polo – with its rather conservative orientation – loses in the symbolic battle against progressive tendencies. But it is nevertheless present in the mainstream. Stylistically, it is reminiscent of Balkan Turbofolk or 1980s Italo Disco. However, like those, it does not fit into the repertoire of high culture.

The Disco Polo music casettes came to the Museum as part of the "Cult Objects" project and the "Disco Relax" exhibition dedicated to the Disco polo phenomenon. Ethnography, despite its important historical dimension, which is even more accentuated in a museum context, is a field interested in the present and in everyday life. Disco Polo has been a subject of interest in academic circles, which has not been helpful in promoting its understanding by the wider public. The role of the Ethnographic Museums is to tell a story about a world that is both familiar and disregarded.

The fundamental dimension linking Disco polo to the broader notion of waste in this case is the marginalisation and symbolic violence mainstream culture applies to competing models. In a hierarchical system, value-free culture and its manifestations are waste, no matter how many people ascribe importance to it. It is eliminated from the mainstream, and if it is present, it is in the form of a pastiche and a caricature that ridicules its participants.

Material

Plastic, cassette tape

Dimension

Length: 10.2cm; height: 64cm; width: 0.12cm.

Inventory number

None

Copyright

PME/NEM

Status

Non-inventory

Image credit

Photograph by Edward Koprowski

Opera chocolate box

- Artist / Maker

- Kraš

- Date production / Creation

- 1984

- Entry in the museum collection

- 2001

- Place of origin

- Zagreb, Croatia, Europe

- Current location

- Museum of Recent History Celje, Celje, Slovenia

A box for life: sometimes, the package is more precious than the goods it contains.

Opera were the premium chocolates in the Kraš range. They were frequently given as a gift to older people for a special occasion or to say thank you for help or a favour. Often the recipient of the gift would not even eat the chocolates, but keep them with the intention of giving them to someone else on another occasion. So they were passed on from person to person, pantry to pantry, and it was quite possible that their shelf-life would expire before anyone actually got to eat the chocolates.

Like other Kraš products, Opera chocolates were sold throughout the former Yugoslavia, and even beyond – according to the information on the box, in 1976 they were awarded a silver medal in London.

The Opera chocolate box was a donation to theMuseum of Recent History Celje. It is important for the museum’s collection as an item that was very familiar in Yugoslav households in the 1970s and 1980s. Many people who lived in Yugoslavia at the time when Kraš were making Opera chocolates would have encountered them in one way or another, either admiring the box on the shelf of a local shop or giving or receiving the chocolates as a gift. It is therefore important as part of the collective memory and of what we call "Yugo-nostalgia".

People did not generally discard an empty Opera box because it was beautiful and luxurious. And it was also big enough to use for various other purposes. People used the box to store documents, photographs, postcards and other mementos or items that had a particular emotional value to them. So Opera chocolate boxes would live on in cupboards and drawers for years after the chocolates had all gone.

Material

Cardboard, artificial velvet / adhesive, print

Dimension

260x370x37 mm

Inventory number

745:CEL;S-12840

Copyright

Museum of Recent History Celje

Status

In storage

Image credit

Matic Javornik

Convolute Shards

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- Early modern period

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1948 - 1955

- Place of origin

- Vienna, Lower Austria, Europe

- Current location

- Austrian museum of folk life and folk art, Vienna, Austria

The curator’s dilemma. Is there any value in a collection without a story?

This is a peculiar convolute or accumulation of objects, special for its quantity and storage volume alone. It consists of a total of 5 314 Schwarzhafner and ceramic fragments, which are stored in almost 100 stacked boxes covering more than 12 linear metres in the depot of the Volkskundemuseum Wien. According to the inventory books of the museum, the shards entered the collection mainly between 1948 and 1955. The shards were found in the Austrian capital, Vienna, and at locations in the surrounding province of Lower Austria. There are no detailed references to individual shards. No scientific or curatorial processing has been recorded. All individual shards were entered into the digital database in 2015, including photos by museum volunteers.

The fragments come from various sites, mainly in Vienna and Lower Austria. While information on the shards is scarce, some remarkable things are known about them. In Vienna, for example, the Albrechtsrampe find site is of particular interest, as 149 individual shards were found there. In March 1945, the inner city of Vienna was bombed and the Albrechtsrampe, a grand staircase in front of the Albertina art museum, was badly damaged. As in other inner cities destroyed during the Second World War, groundbreaking urban planning and infrastructure decisions had to be made during the reconstruction. In 1949, the city of Vienna decided to shorten the historic Albrechtsrampe in order to open the site to car and tram traffic. This led to protests from Vienna’s museum directors, who saw in the reconstruction the danger of losing a historic site of “Old Vienna”, dating from before the city’s urbanisation and industrialisation.

A large number of shards were brought in by Adolf Mais, who had been a research assistant at the museum since 1946. At the beginning of his career, the trained Slavicist, ethnographer and prehistorian had set himself the goal of building up a comprehensive collection of Austrian ceramic finds in order to be able to create a "true picture of our past" based on fragments of material culture. To this end, he collected ceramic shards from various places in Vienna (e.g. finds from cable laying or excavation activities) and Lower Austria (e.g. finds from research in deserted settlements) and brought them to the Volkskundemuseum. The abundance of shards, which were to be collected systematically, was intended to enable the comparison and classification of historical everyday life.

The question of "trash or treasure" arises in several senses with regard to this convolute. First of all, the shards are indeed no longer used; they are broken and unusable objects that would generally be referred to as trash. Their inclusion in the museum collection, however, made the shards once again a potentially valuable resource with the power to shed light on people’s daily lives. They could have given the museum a special position as a place of collection and research in the future. The fact that the shards have remained unused for almost 70 years places them in what is probably a typical intermediate museum category.

Material

Largely unglazed ceramic and black pottery fragments

Inventory number

ÖMV/47025 to ÖMV/47147

Copyright

© Volkskundemuseum Wien

Status

In storage

Image credit

© Christa Knott, Volkskundemuseum Wien; © Carina Neischl, Volkskundemuseum Wien

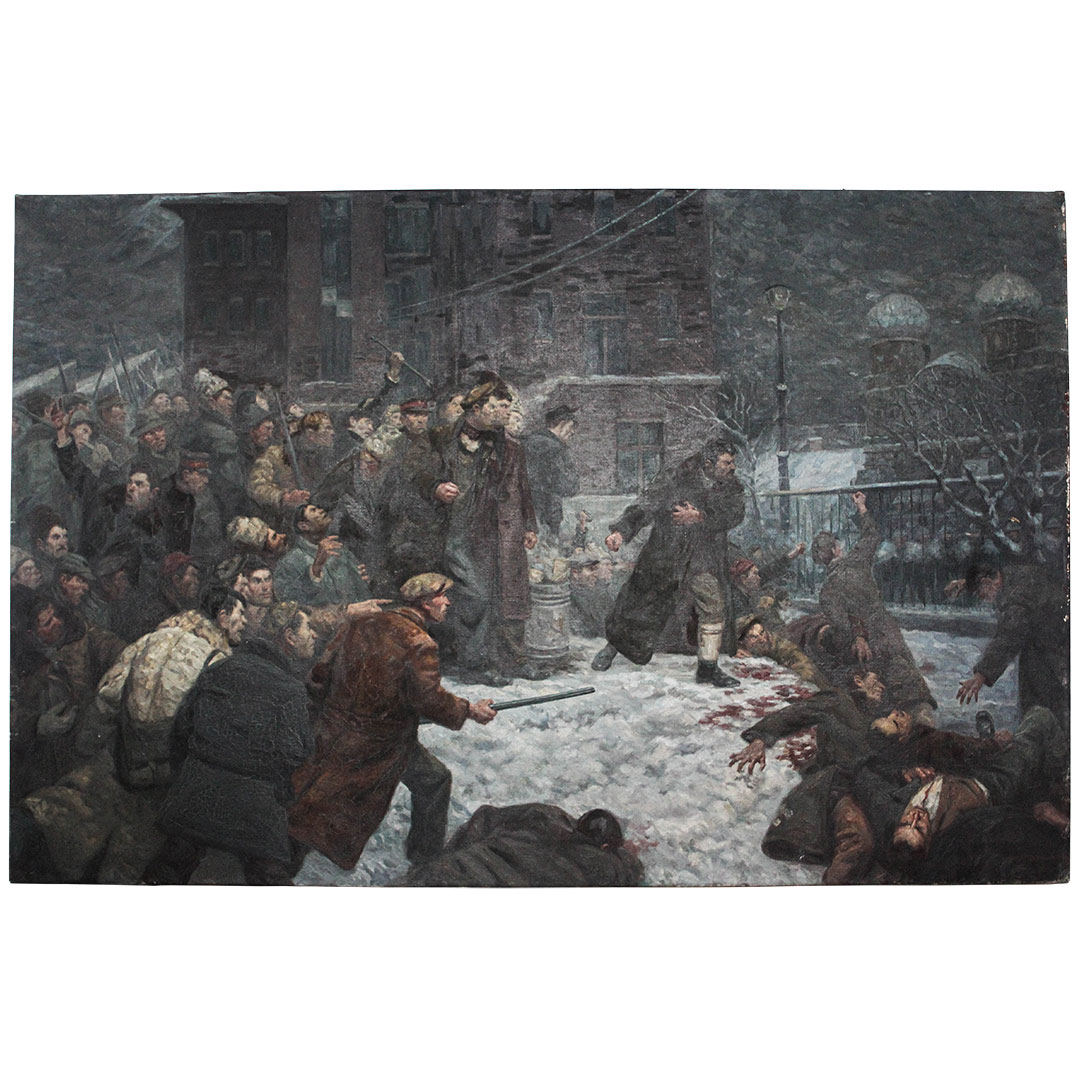

Grivita 1933

- Artist / Maker

- Gábor Miklóssy (1912-1998)

- Date production / Creation

- Fifties (1952)

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1990

- Place of origin

- Bucharest, Romania

- Current location

- National Museum of the Romanian Peasant, Bucharest, Romania

Uncomfortable heritage: a famous painting that gradually slipped into obscurity.

It is a scaled-down replica of a much larger work (310 x 451 cm) painted in 1952 by Gábor Miklóssy (1912-1998) depicting the Grivița rail workers’ strike of February 1933, a landmark event in the history of the Romanian labour movement. The replica was also painted by Miklóssy in the 1950s. This dynamic example of socialist realism depicts 52 individuals, including the electrician Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej (1901-1965), future First Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party (1945-1965) and Prime Minister of Romania. During the Gheorghiu-Dej regime, the painting was widely acclaimed. It was exhibited at the Annual Art Exhibition (1952) and was part of the permanent exhibition at the RPR Museum of Art.

Grivița 1933 significantly contributed to the personality cult surrounding Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. The original painting, which depicts a landmark moment in the history of the interwar labour movement, was exhibited at the Venice Art Biennale (1954), gaining international fame.

As such, it was also used by other communist parties in Central and Eastern Europe for postwar propaganda purposes. A replica was produced in the 1950s at the request of the Hungarian Communist Party Museum and is currently exhibited at the National History Museum in Budapest. The replica held in storage at the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant, was exhibited in Brussels at the 2019 Europalia "Perspectives" Exhibition.

The Grivița 1933 replica was part of the permanent exhibition of the RCP History Museum (ro. Partidul Comunist Român - en. Romanian Communist Party) History Museum. In 1990, the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant inherited both this collection, and that of the former Soviet Lenin-Stalin Museum that had been located in Bucharest between 1955 and 1966. It has kept only a small part of the inherited collections. Among the selected items are around 80 paintings, many of them inspired by socialist realism, including copies of Soviet paintings and also original Soviet or Romanian works, now making up the largest collection of socialist realism art in Romania. The museum keeps them in storage and rarely exhibits them.

During the Ceaușescu regime (1965-1989), Grivița 1933 gradually slipped into obscurity. In the 1970s, the replica was removed from the permanent exhibition at the PCR History Museum and the original was removed from the permanent exhibition at the SRR Museum of Art (ro. Republica Socialistă Română - en. Socialist Republic of Romania), and was irretrievably swallowed up in its storage facility. After 1990, the replica was also to be found in storage alongside other paintings of the socialist realism school. Today, a number of Grivița 1933 replicas are included in collections held by three Romanian art museums but are not readily accessible, having become part of an increasingly uncomfortable heritage.

Material

Oil on canvas

Dimension

127 x 194 cm (L x l, without frame)

Inventory number

C.T-0016

Copyright

Musée national du Paysan roumain

Status

Réserve

Image credit

Vladimir Bulza / © National Museum of the Romanian Peasant