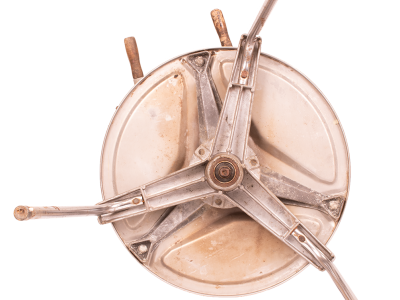

German helmet-bed warmer

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- 20th century (post World War II)

- Place of origin

- Ozzano Taro, Collecchio, Parma, Emilia Romagna, Italy

- Entry in the museum collection

- Terminus post quem 1950

- Current location

- Ettore Guatelli Museum foundation, Ozzanno Taro, Italy

When life gives you helmets… Metal was long considered a precious material, far too valuable to waste.

The items on display in the Ettore Guatelli Museum are a testimony to the everyday but also to creativity, craftsmanship and ingenuity in resolving practical problems by reinventing objects to perform different specific functions. In this case, the person who came across this German military helmet at the end of the Second World War decided to weld a wooden handle to it, making it easier to pick up. Thus transformed, it could be filled with embers and placed together with a "bed wagon" beneath the blankets to keep them warm throughout the night, especially in winter.

Ettore Guatelli saved from oblivion not only this helmet, but also a number of others dating back to World War II. Having been transformed into other everyday practical items, they are now on display in the museum’s "Kitchen Gallery". Together, they provide an insight into a European post-war rural society that relied heavily on creativity and manual dexterity, the necessity of the moment being the mother of highly ingenious invention. In this case, the helmets also prompt reflection on the emotional aspect, the possible feelings of occupied populations towards their occupiers and the desire for a new start following their liberation.

In the 1950s, Ettore Guatelli began increasingly regular visits to waste collectors’ storerooms in the Apennines, gradually laying the foundations for his future museum. From the mid-1970s onwards, his collection of objects grew considerably, unintentionally becoming part of a trend that took off in the seventies and eighties in Italy for the revival and promotion of popular culture. As a result, his museum became a unique and inimitable museum establishment devoted to the demographic, ethnological and anthropological heritage of twentieth-century Italy

Spontaneous design items are a poignant reminder of the "make do and mend" philosophy that provided an albeit less systematic model for modern recycling methods. The need to make use of whatever was at hand proved inspirational when it came to reassembling and reusing items, rather than simply discarding them. As a result, unexpected breakdowns, breakages or simple wear and tear did not necessarily mean that life had to come grinding to a halt.

Dimension

22 (H) 45 (l) 22 (p)

Inventory number

107

Copyright

@Fondazione Museo Ettore Guatelli

Material

Iron, wood

Status

Dislayed

Image credit

Mauro Davoli

‘Giving for helping’ signs

- Artist / Maker

- Les Petits Riens

- Date production / Creation

- Ca. late 1970s – early 1980s

- Entry in the museum collection

- 2022

- Place of origin

- Brussels, Belgium, Europe

- Current location

- House of European History, Bruxelles, Belgique

The little things we throw away could change people’s lives.

The priest Edouard Froidure (1899–1971) founded Les Petits Riens, the makers of these signs, in 1937. Rather than condescending to the poor, charities like his promoted independent self-help. Thus, homeless or unemployed men were able to collect and sell second-hand objects to earn some money. These individuals also lived together in housing provided by the charity. Les Petits Riens’s logo depicts one of these men carrying petits riens (which roughly translates as "small things").

Charities such as this had an impact beyond the disadvantaged groups they were founded to help. At the time, they also influenced patterns of consumption and re-use more widely. Instead of repairing or repurposing old items, people could give them away in good conscience, which slogans such as Les Petits Riens’s ("give to help") deliberately appealed to.

The 19th century saw the birth of the first charities dedicated to the re-purposing and selling of second-hand items. This started with the Salvation Army, founded in London in 1865, and other organisations soon followed. In Brussels, Les Petits Riens was emblematic of the new kind of charitable institutions that these organisations embodied.

Today, Les Petits Riens has 27 shops in Belgium. Across the EU, new profit-driven actors such as online second-hand platforms are expanding. Wearing second-hand clothes is becoming more fashionable across social classes. As Celine, who works for Les Petits Riens, observed, charities both suffer and benefit from this trend. On the one hand, they lose out to competition from for-profit corporations. "Over the last years, many people, before donating, will first try to resell. Therefore, what remains at the end to be given is so often low-quality: (it’s) what one did not manage to sell!" On the other hand, charities are gaining new young customers.

This object originates from a local participatory process conducted during the preparation for Throwaway, in which local waste experts helped to create the exhibition’s contents. These communities of experts contributed to the exhibition through their testimonies and by lending objects (as this one) to be put on display. Les Petits Riens was one of the partners involved and put the House of European History in contact with Celine and other individuals.

Charities such as Les Petits Riens still have an impact beyond the disadvantaged groups they help directly. They still widely influence patterns of consumption, re-use and waste. Wearing second-hand clothes is becoming more fashionable across social classes, in line with concerns about environmentally and socially responsible shopping. Celine, who works for Les Petits Riens, has observed that charities are gaining new young customers "who really come by conviction, to consume differently", for whom "buying second hand is almost activist".

Furthermore, by maintaining and increasing their network of booths dedicated to collecting clothes, Les Petits Riens makes it easy and accessible to donate what one no longer needs. The organisation can help people avoid throwing items in the trash bin prematurely, because donating may be as easy as discarding them.

Material

Wood

Dimension

145,00 x 70,00 x 7,00 cm (H x W x D)

Inventory number

2021.0050.72 and 2021.0050.262

Copyright

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Status

On display in the temporary exhibition Throwaway. The History of a Modern Crisis.

Image credit

Photo 2022 by Regular Studio, © EU, European Parliament

Repaired plate

- Artist / maker

- Unknown

- Date production / creation

- Early 19th century

- Place of origin

- Western Slovakia, Europe

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1896

- Current location

- Austrian museum of folk life and folk art, Vienna, Austria

We can learn a lot about a society by asking what skills it values most highly.

This plate, with its distinctive yellow stag in Haban-Slovak decor, repaired with tinker’s metalwork, was made at the beginning of the 19th century. It is unclear exactly when the repair was made. Slovak tinkers, called "Rastelbinder" (from the rust of wire goods), were part of the visual and acoustic cityscape and the life of the alleyways and courtyards of the Danube Monarchy until the 20th century. The best-known of the Slovak tinker groups roamed all over Europe, mending broken pottery and selling homemade household utensils such as sieves, ladles, baskets and mousetraps. Their characteristic Slovakian costumes and the colourful range of goods they carried made them a conspicuous sight, especially in Vienna.

In the Austrian part of the Danube Monarchy, the tinkering trade was strictly regulated in the middle of the 19th century. However, populations from the economically weaker areas, where agriculture did not provide a sufficient livelihood, were granted licence – under strict conditions – to make much-needed income by practising this trade. Certain regions began to specialise in certain goods and/or services, as was the case with the tinkers from western Slovakia (then Upper Hungary). The men from these areas initially moved as itinerant hawkers to neighbouring areas in Bohemia or southern Hungary. Later they were to be found in all areas of the Danube Monarchy. Their talent for languages led them from Italy to Russia and Constantinople, and finally also in their thousands to the US.

The plate came to the Volkskundemuseum in 1897 as a gift (Pf. Maluchinsky). It was of interest to the museum in two respects: firstly, as a remarkable example of a certain type of faience with Haban decor; and secondly, because of the tinker’s repair. The trade and the craft of the tinkers were already in decline at the time it came to the museum. The availability of new, cheaper and more resistant materials and products had greatly diminished demand for their activities. On the other hand, the reputation of the tinkers as "Viennese types", and their stereotyped and clichéd representation in genre and popular painting, had risen sharply. Around 1897, for example, the "Rastelbinder" was a popular costume at fancy dress parties, and in 1902 they were further memorialised in the operetta "Der Rastelbinder", by Franz Lehár.

The plate with tinker’s metalwork has an interesting connection with rubbish in several ways. One is that it demonstrates the historical culture of repairing. The things that tinkers mended, i.e. household goods made of ceramics or metal, were expensive when they were first made, and for many people they were valuable possessions that were passed down through generations. On the other hand, the plate serves to remind us of the people who worked with broken things. Although the tinkers were in demand for their craft, their standing in society was low. Their lives and working methods were characterised by migration far from their families, child labour, poor living conditions and ethnic discrimination. The resident population of Vienna tended to perceive them as annoying peddlers or even beggars.

Material

Faience/brush decor

Inventory number

ÖMV/6.215

Dimension

7x32,2cm

Copyright

Volkskundemuseum Wien

Status

In storage

Image credit

© Volkskundemuseum Wien

Bronze Age hoard from Wöllersdorf

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- 1000-800 BCE

- Place of origin

- Wöllersdorf, Austria, Europe

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1902, purchased from an antiquities-collector

- Current location

- Museum of Natural History Vienna, Austria

There’s more to hoards than meets the eye. What can we learn from a load of prehistoric junk?

A total of 61 pieces of bronze weapons and equipment weighing more than 3 kg were deposited in Wöllersdorf, Austria. The hoard consists of bronze scraps and object fragments that are typical of the early part of the Late Bronze Age (1000-800 BCE). They contain a wide variety of broken objects, including weapons, axes, tools, jewellery, pieces of metal and wires. Most of the objects had been damaged, and many had been deliberately fragmented.

In the Late Bronze Age (around 1000 BC), deposited metal objects were a typical phenomenon. This included weapons, tools, vessels, jewellery, wagon parts and even ritual equipment, and including both intact and beautiful pieces and fragments and raw metal. They have been found in striking landscapes, in settlements, at or in bodies of water and in remote places. Many researchers have interpreted them to be the storage hoards of itinerant bronzesmiths or traders because of their material value, or as hiding places in times of war. However, hoards containing broken objects may also be the remnants of a widespread recycling economy, indicating a careful and efficient use of resources.

The artefacts were found in the small village of Wöllersdorf, Austria at the very beginning of the 20th century. They were then purchased by the Natural History Museum Vienna in 1902. Unfortunately, the documentation on the person who found the Wöllersdorf hoard has been lost.

The hoard of fragmented bronze objects demonstrates that they were supposed to be re-smelted to make new things out of the material. 3000 years ago, long before the Industrial Revolution, the gathering of raw materials and the production of items were time-consuming processes, and the recycling and re-use of these materials has been a common practice for most of human history. This especially, but by no means exclusively, applies to periods in which resources were scarce (e.g. war- and post-wartimes).

Material

Bronze

Inventory number

NHM_PA_37392-37411

Dimension

Item sizes range from 3.5 to 14.5 cm large

Copyright

Natural History Museum Vienna

Status

On display

Image credit

Natural History Museum Vienna, photos: Alice Schumacher

Textile recycling in the Iron Age

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- 800-600 BCE

- Place of origin

- Hallstatt, Austria, Europe

- Entry in the museum collection

- 1967 and 1990, archaeological excavations by the Department of Prehistory

- Current location

- Museum of Natural History Vienna, Austria

Iron-age practice: Tearing-up cloth in stripes and reusing it as binding material.

The object is a fragment of a yellow tabby textile with a knot and the remains of two olive-green twill bands knotted together. Various textiles have been found in the Iron Age layers of the Hallstatt salt mine (c. 800-600 BCE). Some of the textiles had been deliberately torn into stripes and re-used as makeshift binding material.

Making textiles with all the different workflow steps (raising sheep, shearing, spinning, weaving) was a time-consuming task thousands of years ago, without the use of modern tools. The careful and responsible handling and use of textiles was important. We are not sure who was responsible for making textiles, although textile tools like spindle whorls and loom weights are usually found in women’s graves. The textiles from Hallstatt were found in a salt mine and some show characteristic traces of tears and knotting. This was surely not the intended primary use of this textile, which may have been made to be part of a garment; but it was eventually recycled and used for repair work.

From different contexts in prehistoric Central Europe, we know that textile material was deliberately torn into strips and re-used, e.g. as makeshift binding material, which is indicated by characteristic knots. Clear evidence for that has come from two prehistoric salt mines in Austria, Hallstatt and Dürrnberg, broadly dated to the 1st millennium BCE. Usually, strings and ropes made of various trees and grasses were used primarily as binding materials in the salt mines. If these were not at hand, textile strips, leather strips or even young elastic twigs were used.

The Natural History Museum Vienna has been conducting research in collaboration with the town of Hallstatt for more than 100 years. The museum has an onsite field office in the town from which scientists continue to carry out their work. Each year, since the 1960s, regular scientific archaeological excavations have taken place at the Hallstatt salt mine. The artefacts excavated there immediately enter the museum’s collection.

Textile production was a time-consuming process before the Industrial Revolution and textile recycling has been a common practice for most of human history. This especially, but by no means exclusively, applies to periods in which resources were scarce (e.g. war- and post-wartimes). Textiles have been regularly altered or adapted for new uses throughout history. Various examples ranging from the Bronze Age to the Early Modern period demonstrate the different purposes for which recycled textiles have been used, including as caulking material for ships, as stuffing for cavities of medieval castles and as sealing for water management in copper mines. Textiles have also been used as coverings and for hygienic purposes and have served as various kinds of makeshift material. Clothing recycling involves the re-working of garments in various ways.

Material

Sheep wool

Dimension

Yellow textile: 11.5x4.5 cm; green textile: 29x10 cm (both pieces together)

Inventory number

NHM_PA_77.334 (HallTex 78) and NHM_PA_89.724 (HallTex 121)

Copyright

Natural History Museum Vienna

Status

In storage

The Glove – back home again!

- Artist / Maker

- Folk art

- Date production / Creation

- Home-made handicraft 1930s

- Entry in the museum collection

- The 2000s

- Place of origin

- Muhu island, Estonia, Europe

- Current location

- Estonian national museum, Tartu, Estonia

Knitted in Estonia, repatriated as waste from Germany.

In modern Nordic countries gloves are important everyday ethnographic items in our homes, where beautiful traditional patterned gloves are used side by side with modern designer accessories. We all know that the main purpose of gloves for Estonians is to protect them from the cold. Woollen gloves were made in Estonia as early as the Bronze Age. Proof of use of knitting needles in Estonia comes from a glove fragment from the 14th century. The first types of gloves were needle mittens (made with a specialist needle). For centuries, glove wearing has had its own customs and traditions, playing an important role in wedding etiquette. In everyday life gloves also played a role in folk medicine; the warm gloves young men were given when they were sent to war may have been lifesavers in the winter cold; they may have been precious items from home for those fleeing from war across the sea in the 20th century.

‘I found this ethnographic glove that had been knitted on the beautiful Muhu island located on the east coast of the Baltic Sea in the Veski Street second-hand shop in Tartu. I asked where their goods came from and they said Germany. I bought the glove for 5 Estonian crowns and gave it to the museum. I wondered how this glove ended up in Germany. In fact, Germany had big refugee camps for Estonians – did an Estonian who ended up in the resettlement camp in Germany take their warm gloves with them? Or was it some soldier who was in a battle on Muhu and received them as hand warmers? In any case, I had all sorts of thoughts about how that glove ended up as waste and travelled back to Estonia as humanitarian aid. I put that beautiful ethnographic glove on display in 2009 as part of the National Museum’s exhibition to mark its 100th anniversary, as an example of how objects end up in the museum.’

Reet Piiri, ethnologist / Estonian National Museum / 2022

Estonia, Germany, resettlement camps after WWII, new retail network of the 1990s and the EU

The collection of traditional Estonian patterned gloves belonging to the Estonian National Museum is exceptionally plentiful – 4 116 in total –, which includes gloves with beautiful Estonian patterns and intriguing stories that have reached the collection from the Estonian diaspora. Traditional patterned gloves are a good exhibition material: techniques (knitting with needles), ethnographic peculiarities between Estonian parishes, colour teaching (use of wool), pattern as a semiotic system, provide a lot of clues on the meaning of folk costumes and on how these were worn that the museum can use in its educational programmes.

Humanitarian aid system in Europe; there were huge quantities of textile garments brought to newly re-independent Baltic countries, to Estonia; in Germany they could have been left by waste containers or in collection boxes; they may have travelled from the home of a European person who was moving or renovating to the home of an Estonian person and not to landfill.

Material

Sheep’s wool

Dimension

Width: 12.0 cm; Length: 25.0 cm

Copyright

Estonian National Museum

Status

Textile storage / collections

Image credit

Estonian National Museum

Boot

- Artist / Maker

- Unknown

- Date production / Creation

- 20 century

- Entry in the museum collection

- Terminus post quem 1950

- Place of origin

- Ozzano Taro, Collecchio, Parma, Emilia Romagna, Italy

- Current location

- Ettore Guatelli Museum foundation, Ozzanno Taro, Italy

As the old saying goes, you can tell a lot about a person from their shoes.

The Ettore Guatelli Museum is home to a boot once worn by a young farmer – a boot with a patchwork of stories entwined. The boot tells the stories of the countless times it was worn, patched up and mended to accompany the farmer as he laboured in the fields, of the time it was discovered in an attic by a collector who brought it to the Ettore Guatelli Museum, and also of the time it met two photographers from Rome, who shot it for a poster that would see it travel round the world as the poster child for Guatelli’s initiative to set up a museum to house his finds that bear witness to the craftsmanship in rural communities that would let nothing go to waste.

The Ettore Guatelli Museum’s boot opens up many potential avenues of thought to be explored. The first might be for us to look beyond the local, beyond the Emiliana countryside, to the life and work of rural communities throughout Europe and across the globe. Over the course of history, who knows how many boots will be repaired and resoled so that they may reach their potential and tread who knows which roads. And today, ‘the boot’ might also come to symbolise the step it takes to transcend borders, envision a common path and harness the value of freedom.

In the 1950s, Ettore Guatelli began increasingly regular visits to waste collectors’ storerooms in the Apennines, gradually laying the foundations for his future museum. From the mid-1970s, his collection expanded considerably, becoming unintentionally part of a growing trend in the seventies and eighties for the revival and promotion of popular culture. As a result, his establishment became a unique and inimitable demographic, ethnological and anthropological heritage museum of 20th-century Italy.

It was in 1994 that Ettore Guatelli published an essay entitled ‘Waste at the Museum’ in the fifth issue of the periodical ‘Ossimori’. In it, he addressed a highly topical issue, now fast becoming an emergency, stressing the need to reflect on the nature of waste and discarded objects and, more to the point, the recovery and recycling thereof. It is here and even more so in waste disposal that the historic key to genuine ‘democracy’ is to be found.

Material

Boot that has been repaired and resoled countless times using wire and nails

Material

24 x 11x 14

Copyright

@Fondazione Museo Ettore Guatelli

Status

On display

Image credit

Mauro Davoli

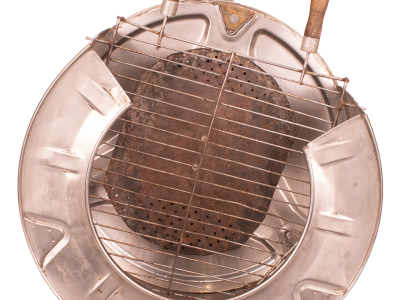

Grill made from a washing machine drum

- Artist / Maker

- Stanisław Chełstowski

- Date production / Creation

- No data/21st century

- Entry in the museum collection

- 2016

- Place of origin

- Janów Podlaski, Lubelskie Province, Poland, Europe

- Current location

- National Ethnographic Museum in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

Necessity is the mother of invention. It can also be the enemy of waste.

It is difficult to determine precisely when the fashion for barbecuing arrived in Poland. After all, the thermal treatment of meat is as old as the traces of the first campfire. For the anthropologist, a DIY grill is a story with at least a few different threads. The first is as a popular way to spend leisure time, for which the grill and the characteristic smell of burning charcoal have become a symbol: mates, beer and music. The venue is irrelevant – it could even be the balcony of a block of flats. Another aspect is the formation of Poles’ eating habits. Currently, the barbecue is the first victim of the post-meat policy of vegans. Waste management in Poland is also an important thread. If not for the grill made from the drum, the entire washing machine would have ended up being dumped in the forest.

The object and its character are in no way unique or endemic to Polish culture. Both the motivations for its construction and its purpose lie deep within human nature: creativity, hunger and eating together. It is only the cultural layer, i.e. how, with whom, where and what we eat, that seems to set us apart: there is no better thing than a barbecued pork neck cured in honey-mustard sauce and a cold beer – oh, I can already hear the voices of dissent.

The context for the contemporary and DIY grill is a collection of everyday objects framed by the history of Polish rural culture, which is marked by chronic shortages. This scarcity unleashed creative and adaptive potentials and, with the flourishing of the capitalist-consumer economy, recontextualised such creations by embedding them in the field of hobbies and skills. Such products were often associated with the lower economic status of the maker.

The basic element linking the object to the broader concept of waste in this case is reusing and giving a new function to already-existing objects. If we think of it as a product of a culture of scarcity, then a whole class of concepts comes into play that refer to a human being relegated to the category of junk – a human being who lives outside the margins of social control.

Material

Steel, cutting, welding, cutting out and screws

Dimension

Height 74cm; diameter 45.5cm

Inventory number

PME 58930/1-2

Copyright

PME/NEM

Status

In storage

Image credit

Photograph by Edward Koprowski