Mapping Europe

Where does Europe begin and where does it end? Since ancient times it’s described as being distinct; culturally and historically shaped – yet geographically, Europe and Asia are one continent.

Europe’s interest in maps and map-making has a long and varied history reaching back to ancient Greece and Rome. The discovery of sea routes to the Americas in the 15th century changed not only Europeans’ views of the known world but also how they saw themselves.

Virtual Tour

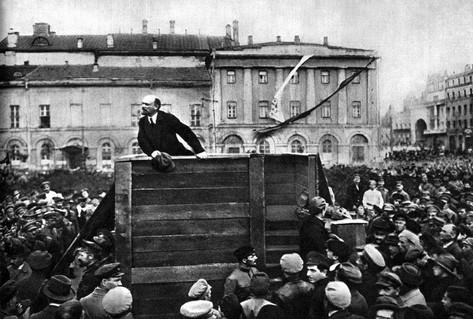

Works by ancient geographers such as Claudius Ptolemy (c.90-c.170 CE) give us glimpses into their known world. Only parts of Europe, Asia and North Africa are represented. Ptolemy used a system of coordinates to locate specific places. His maps remained the basis for European cartography beyond the 15th century.

World-map in Ptolemy’s geography

Italy, ca. 1454

Ioannis Rhosos

Illustrated manuscript

Replica of the original in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice, Italy

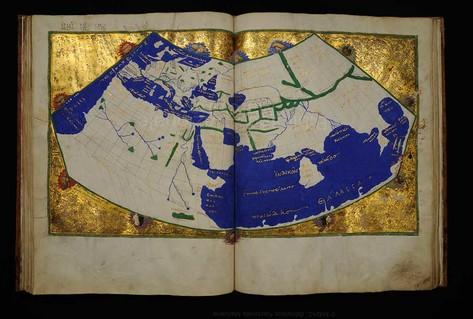

Maps created during the Middle Ages often disregarded geographical accuracy in favour of Christian messages and symbolism. In the Renaissance, the continent of Europe was represented as the Virgin Mary: an expression of its Christian identity.

Europe as the Virgin Mary

Basel, Switzerland, (1588) 1628

From Sebastian Münster’s (1488–1552) “Cosmographia”

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

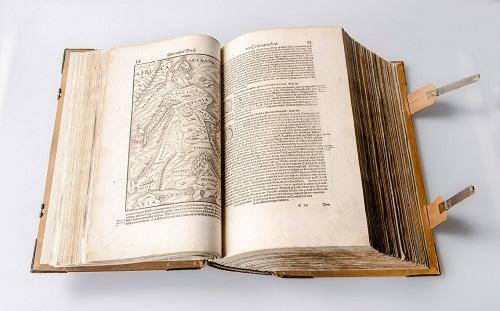

Our view of the world is usually determined by where we live. World maps created outside Europe make this strikingly clear; the continent suddenly seems distant and small.

World map

China 2012

SinoMaps Press

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

The myth of Europe

Europa, a mythical princess from Phoenicia – today´s Lebanon – is abducted by the Greek god Zeus, who appears to her in the form of a white bull. Having fallen in love with her beauty, he takes her to the island of Crete.

Europe’s name has been associated with this myth from antiquity to the present. It appears in art, literature, religion and politics, where the story and imagery are often reinterpreted to reflect the issues of the day.

In the Greco-Roman world, Europa riding on the back of Zeus was a recurring subject on ceramics, wall paintings and mosaics. The export of Greek vases also contributed to the myth’s spread.

Europa riding the bull

Metope from temple Y, Selinunte, Sicily, ca. 580-560 BCE

Replica of the original in the Museo Archeologico Regionale Antonio Salinas, Palermo, Italy

The myth of Europa has often been used to comment on European politics. Such representations range from early 20th‑century attempts at pan-Europeanisation to the horrors and violence of devastating wars.

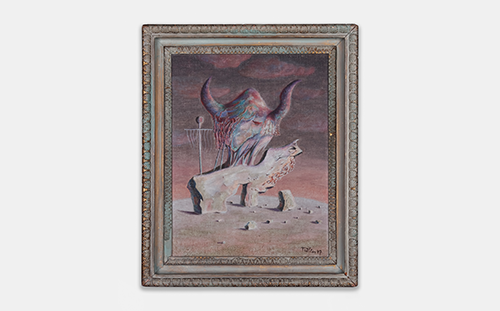

“Barbaropa”

Germany, 1947

Heinz Trökes (1913–1997)

Oil on canvas

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

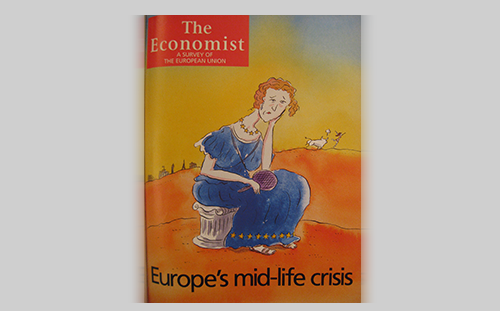

More recent interpretations of the myth of Europa see it as a symbol for European integration. It has taken the form of a watermark on currency and been used to illustrate political issues such as the euro crisis.

“Europe’s mid-life crisis”

The Economist, London, United Kingdom, 31 May 1997

Satoshi Kambayashi

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

European heritage

What binds the continent together? What could be regarded as European heritage?

Europe is more than the addition of national histories, but is it a civilization and culture characterised by particular traditions and values developed through history?

There are basic elements which are originally European and have spread all over the continent. Can these be considered distinct hallmarks of European culture? If so, what parts of this European heritage should we preserve, what do we want to change, what should we contest?

From its origins in the Middle East, Christianity spread across Europe to become immensely influential and a defining feature of 'Western' civilisation. Today, European values, traditions and culture still reflect this long Christian heritage.

Carved figure of Pope St. Martin’s Church Utrecht

The Netherlands

late 15th century

Museum Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, Netherlands

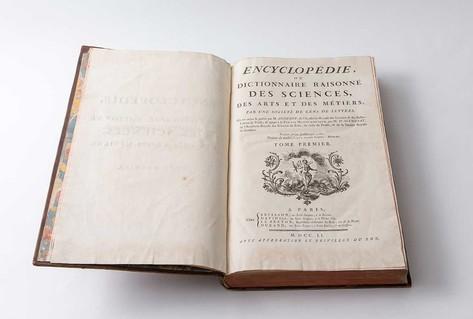

The eighteenth century ‘Age of Enlightenment’ was a watershed in the cultural and political development of Europe. Emphasising the value of reason and rational thinking, it inspired dramatic developments in science, philosophy, society and politics.

Diderot’s and d’Alambert’s Encyclopaedia

Paris, France 1751-1772

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Democracy is a form of government that gives self-determination to citizens, with political decisions made by the majority of the people. It was only in the twentieth century that European democracies extended the right to vote to include all adult citizens.

Ballot selecting Themistocles for exile

Athens, Greece, 5th Century BCE

Clay

ΜουσείοΑρχαίαςΑγοράς / Museum of the Ancient Agora, Athens, Greece.

Memory

If we remember the past can we avoid repeating its mistakes? Memory is seen as essential. Whether for individuals or for social groups it is the basis of learning and self-awareness.

Yet, memory is a complicated phenomenon. It is selective and inseparably aligned with oblivion. Our memoires are a vital part of history and deeply influence our present and our future. How we remember the same history constantly changes.

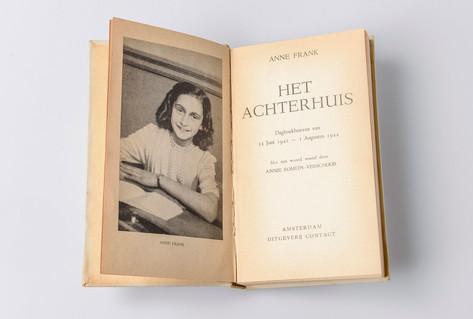

Memory is subjective and highly influenced by circumstances. The diary of Anne Frank, a young Jewish girl hiding in Amsterdam during Nazi occupation has become a book of world renown. Testimonies like this which personalise history can sometimes tell more about history than historiographical analysis.

"Het Achterhuis”/ “The Diary of a Young Girl

Anne Frank (1929-1945)

Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1947

House of European History, Brussels, Belgium

Memory depends on historical context. Sometimes it motivates revenge, at other times it lead the way to reconciliation. The highly symbolic moment at this Great War commemoration attended by Francois Mitterrand and Helmut Kohl represented the end of the historic enmity between France and Germany.

Joint Battle of Verdun Commemoration Verdun

France, 22 September 1984

Photograph

ullstein bild - Sven Simon

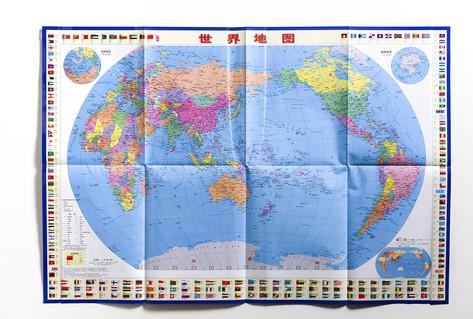

Memory can be manipulated to erase and undermine. The ‘airbrushing’ from history of certain people has been the hallmark of totalitarian regimes. Having fallen foul of Joseph Stalin after 1929 Leon Trotsky and Lev Kamenev were removed from the iconic photograph of Lenin giving a speech.

Trotsky and Kamenev were at Lenin’s side, later both men removed by censors

Moscow, Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, 5 May 1920 / after 1929

Photograph/ Doctored Photograph

Getty Images, Amsterdam, Netherlands