Virtuele rondleiding I – Fake For Real

Tijdens deze tentoonstelling krijgt u een overzicht van vervalsingen door de eeuwen heen. De volgende vragen worden hierbij gesteld: Hoe en waarom zijn ze ontstaan? Wat zijn de gevolgen ervan? Hoe is de waarheid uiteindelijk aan het licht gekomen? We willen laten zien dat vervalsingen al sinds mensenheugenis bestaan en dus niet alleen van deze tijd zijn. We kijken bovendien hoe we ons beter kunnen wapenen tegen misleiding en manipulatie.

De tentoonstelling Fake For Real in vogelvlucht

Hoe baanden onze voorouders zich een weg in een wereld doordrenkt van rotsvaste geloofsovertuigingen? Hoe bepaalden zij wat wel of niet echt was? Al eeuwenlang houden politieke en religieuze kringen elkaars aanspraak op macht en legitimiteit in stand. In elk tijdperk wordt het meest waardevolle nagemaakt, vandaar dat de grootste vervalsingen in de middeleeuwen van religieuze aard waren.

Geloofwaardige vervalsingen – een reeks virtuele rondleidingen van het Huis van de Europese geschiedenis

Van nature uit willen we alles om ons heen onderzoeken, verklaren en beter begrijpen. Daarvoor gebruiken we de technieken waarover we beschikken. We gaan het nu hebben over vervalsingen in verband met de geleidelijke uitbreiding van de horizon van de Europeanen: van geografische ontdekkingen tot moderne wetenschap.

Vervalsingen in de wetenschap – een reeks virtuele rondleidingen van het Huis van de Europese geschiedenis

We zijn nu aangeland in het spannende tijdperk van natievorming. Ten tijde van de 18e en 19e eeuw werd Europa gekenmerkt door turbulentie en transformatie. Imperia stortten ineen en op de ruïnes daarvan ontstonden nieuwe naties. Dit deel van de tentoonstelling gaat over vaderlandslievende vervalsingen, samenzweringstheorieën en het valse bewijsmateriaal dat in het Dreyfusproces werd gebruikt.

Vaderlandslievende vervalsingen en samenzweringstheorieën – een reeks virtuele rondleidingen van het Huis van de Europese geschiedenis

Virtuele rondleiding II – Fake for Real

You may have heard this phrase: truth is the first casualty of war. And although we cannot establish its exact origin – we must acknowledge the wisdom it contains. In this section of the exhibition we explore the types of fakes and forgeries used during wartime, and the 'good' side of forging: the ethical counterfeit, the legitimate fake.

Fake For Good - House of European History virtual tour series

Deze aflevering draait om de vraag: is het mogelijk om iemands bestaan uit de geschiedenis te wissen op bevel van de machthebbers? Waarom zou staatspropaganda bij dergelijke praktijken betrokken zijn?

Manipulatie van het geheugen - Virtuele rondleiding door het Huis van de Europese Geschiedenis

In deze laatste aflevering staan we stil bij meer hedendaagse kwesties: de vrijheid om te schrijven en te publiceren wat men wil. Is dat een absoluut recht of moet er aan bepaalde beperkingen worden gesteld? Zijn sommige teksten puur destructief of is vrijheid van meningsuiting altijd het beschermen waard? U heeft waarschijnlijk wel eens gehoord over haatzaaiende uitlatingen en nepnieuws in de context van internet en sociale media, maar deze discussie is allesbehalve nieuw...

De evolutie van nepnieuws – virtuele rondleiding door het Huis van de Europese geschiedenis

Mensenrechten in Fake for Real - rondleiding door de curatoren

Ter gelegenheid van de Dag van de Mensenrechten 2020 duiken we in onze tentoonstelling Fake For Real om te onderzoeken hoe vrijheid van meningsuiting, nepnieuws en desinformatie doorheen de Europese geschiedenis met elkaar in wisselwerking zijn geweest.

Met curator Joanna Urbanek

In onze tweede video voor de Dag van de Mensenrechten kunt u samen met ons de tentoonstelling Fake For Real bezoeken om te zien hoe de Dreyfus-affaire en antisemitische daden het recht op een eerlijk proces ondermijnden en een internationaal schandaal veroorzaakten.

Met curator Simina Badica

Regeren en bidden

Waardoor wordt macht legitiem? Sinds mensenheugenis houden politieke en religieuze kringen elkaars aanspraak op macht en legitimiteit in stand. Romeinse keizers werden goden; pausen hadden wereldlijke macht; de aanwezigheid van stoffelijke resten van heiligen vergrootte het prestige van heilige plaatsen. Een keizer met een smetteloos blazoen, de tot in de puntjes verzorgde administratie van de paus, de fysieke aanwezigheid van een krachtige heilige – dit klinkt allemaal bijna te mooi om waar te zijn. Gelukkig hoeven we de vertekende getuigenissen over het verleden niet te herhalen. De feiten zijn door dappere en nieuwsgierige personen aan het licht gebracht.

Marmeren buste van keizer Geta, vernield met een beitel in het kader van damnatio memoriae

Voor Romeinse keizers, die erop gebrand waren om godsdienst en politieke macht te combineren, was de kroningsceremonie het hoogtepunt van hun roem: ze werden goddelijk en onsterfelijk. In schril contrast daarmee stond de ultieme straf: geschrapt worden uit de geschiedenis. In de moderne tijd werd de term damnatio memoriae gemunt om deze praktijk te beschrijven. Veroordeelden werden uit de geschiedschrijving verwijderd, hun testament werd nietig verklaard en hun beeltenissen werden vernietigd. In het geval van Geta – die werd vermoord op bevel van zijn broer en medekeizer Caracalla – stond alleen al op het noemen van zijn naam de doodstraf.

© Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia

De kroniekschrijver Adémar van Chabannes beweerde dat de heilige Martialis, een bisschop uit de derde eeuw die begraven ligt in Limoges, een van de apostelen moest zijn geweest. Adémar overtuigde veel mensen en vergrootte daarmee het prestige van de abdij van de heilige Martialis, maar een rondreizende monnik, Benedictus van Chiusa, betwistte dit verhaal aangezien het niet werd vermeld in de vroegchristelijke traditie.

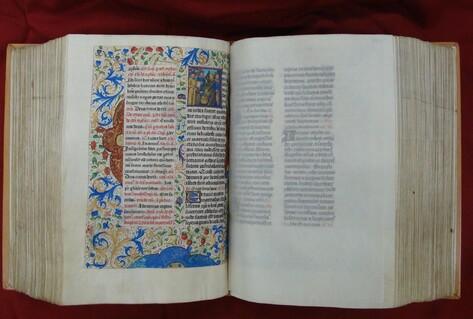

Gebedenboek met een afbeelding van de heilige Martialis als een van de aanwezigen bij de vermenigvuldiging van de broden

© Les silos, maison du livre et de l’affiche, Ville de Chaumont, Frankrijk

Begrip van de wereld

De uitvinding van de drukpers luidde een nieuw tijdperk in, nu informatie op ongekende schaal beschikbaar kwam. Een overvloedige hoeveelheid informatie is echter geen garantie voor nauwkeurigheid. Personen die roem en geld najoegen, verspreidden graag valse informatie bij een publiek dat alles wilde weten over de laatste ontdekkingen. Zelfs de geschiedenis van de wetenschap kent opzettelijke vervalsingen. Wetenschappelijke inzichten kunnen telkens weerlegd en gecorrigeerd worden – dat is de kern van de wetenschap waarmee zij zich onderscheidt van andere manieren om de wereld te verklaren.

Figuur van een ningyo, een “menselijke vis”

Kaartenmakers en schrijvers illustreerden hun werk vaak met afbeeldingen van zeemonsters en fantasiewezens die volgens de overlevering verschenen aan zeelieden of hen zelfs aanvielen. Zelfs Columbus beweerde drie zeemeerminnen te hebben gezien, die “niet zo mooi waren als ze altijd worden afgebeeld”. Tot in de negentiende eeuw waren er nog Japanse “zeemeerminnen” te zien in rariteitenkabinetten en musea in Europa en Amerika. In de Japanse cultuur ging men ervan uit dat ningyo’s mystieke krachten hadden.

© Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen, Nederland

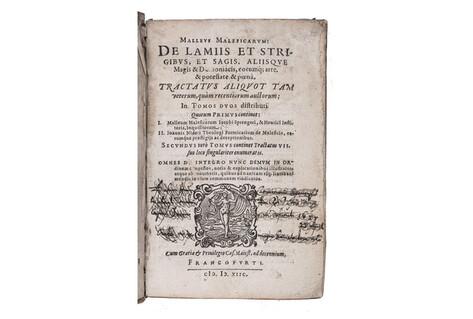

De Heksenhamer – een handboek voor de heksenvervolging - Frankfurt, 1588

De uitvinding van de drukpers rond 1440 leidde tot een stortvloed aan informatie en desinformatie. Gebrek aan controle over de inhoud bracht een gevoel van onbehagen teweeg dat lijkt op de bezwaren die we nu hebben tegen nepnieuws, een verdraaide voorstelling van de werkelijkheid en haatzaaiende taal. De opkomst van de drukpers maakte veel slachtoffers. De populariteit van teksten over hekserij bracht een golf van vervolgingen teweeg en joeg over een periode van meer dan twee eeuwen duizenden zogenaamde “heksen” de dood in. Tegelijkertijd nam de geletterdheid onder de Europeanen toe en hadden zij dus toegang tot boeken, pamfletten en kranten waarmee ze zich konden wapenen om burgerlijke vrijheden te verwerven en de loop van de geschiedenis te veranderen.

Huis van de Europese geschiedenis, België

Anoniem briefje waarin apotheker David Welman ervan wordt beschuldigd een heks en weerwolf te zijn*

Na een plaatselijke ruzie doken veel van dit soort briefjes op in het Duitse Lemgo. Na twee rechtszittingen werd Welman terechtgesteld.

Lemgo, 1642

© Stadtarchiv Lemgo, Duitsland

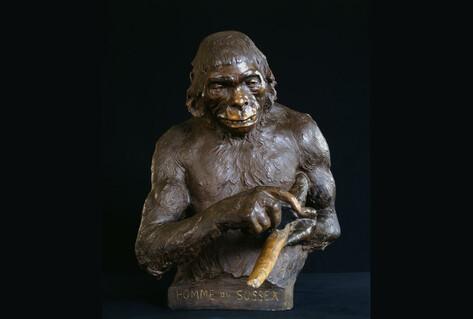

Piltdown Man

Wetenschap streeft naar feitelijkheid aan de hand van empirisch onderzoek. Toch geven wetenschappers in hun werk ook onvermijdelijk blijk van partijdigheid. Anderen verdraaien met opzet onderzoek voor persoonlijk gewin. Charles Dawson was zo iemand. Het duurde veertig jaar voordat het bedrog van de Piltdown-mens uit 1912 aan het licht kwam, omdat het verhaal ingang vond bij paleontologen die erop gebrand waren om hun eigen theorieën bevestigd te zien. De onthulling van dit bedrog is tekenend voor de kracht van de wetenschappelijke methode. In tegenstelling tot religieuze doctrines of ideologieën kan wetenschappelijke kennis worden weerlegd of bewezen.

Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen.

Verenigen en verdelen

Namaakartikelen en vervalsingen waren krachtige instrumenten in het ontstaansproces van etnische en nationale identiteiten in de achttiende en negentiende eeuw. In heel Europa werden nationale bewegingen versterkt door “vaderlandslievende” namaakartikelen in combinatie met echte historische ontdekkingen. Voor het ontstaan van moderne naties was een gedeelde geschiedenis nodig, maar ook gemeenschappelijke vijanden. Vervalste documenten, samenzweringstheorieën en juridische dwalingen werden gebruikt om de zondebokken van de samenleving aan te wijzen en te veroordelen, met alle dramatische en langdurige gevolgen van dien.

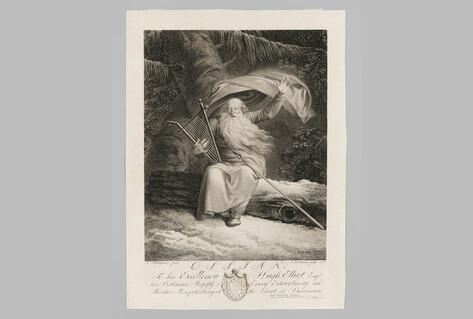

Koperen gravure van Ossians zwanenzang, door Johan Frederik Clemens - Kopenhagen, 1787

Geschiedenis, literatuur en kunst werden belangrijke politieke instrumenten bij de totstandkoming van nationale identiteiten in het Europa van de achttiende en negentiende eeuw. De behoefte om “de leemtes op te vullen” gaf aanleiding tot talrijke vervalsingen. Met elke “ontdekking” kon men zeer ver teruggaan in de geschiedenis van een volk en zodoende de loftrompet steken over de eigen culturele superioriteit. Veel verhalen werden verteld door een nationale “Homerus” en gingen erover dat het eigen land de bakermat van de Indo-Europese beschaving vormde. Deze verhalen hebben lange tijd veel invloed gehad, ook nadat ze verzonnen bleken te zijn.

Kopergravure van Ossians Zwanenzang, door Johan Frederik Clemens, Kopenhagen, 1787

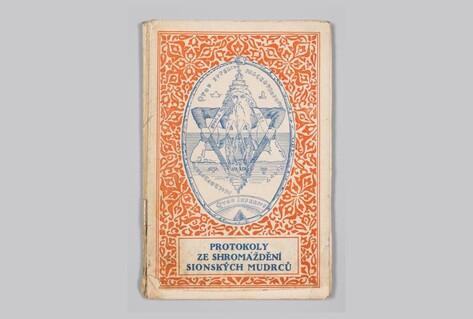

Tsjechische vertaling van de Protocollen van de Wijzen van Zion - 1925

Een complottheorie stelt dat een geheime, zeer invloedrijke groep mensen verantwoordelijk is voor dramatische en schijnbaar onverklaarbare gebeurtenissen. De Protocollen van de Wijzen van Zion, gepubliceerd in het tsaristische Rusland in 1903, beweerden de joodse plannen voor wereldheerschappij te onthullen. Deze vervalsing in de vorm van een complottheorie werd de meest invloedrijke antisemitische tekst van de afgelopen honderd jaar. Hoewel het al snel werd ontkracht, verspreidden de ideeën zich, met verwoestende gevolgen.

© Huis van de Europese geschiedenis, België

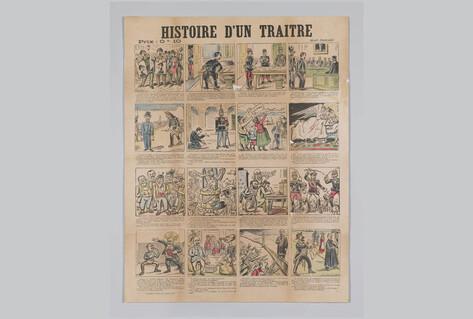

Poster met uitleg over de Dreyfus-affaire bij de tentoonstelling ‘Geschiedenis van een verrader’ - Frankrijk, 1899

In 1894 is er een document gevonden waarin werd aangeboden Franse militaire geheimen aan Duitsland te verkopen. Dit misdrijf mocht niet onbestraft blijven. In grote haast werd er een aanklacht in elkaar geflanst tegen Alfred Dreyfus, de enige Joodse officier in de generale staf van het Franse leger. Op basis van vervalste documenten, een “geheim dossier” en vergezochte “deskundigenverslagen” werd Dreyfus beschuldigd van verraad en veroordeeld tot militaire degradatie en levenslange verbanning. De “Dreyfusaffaire” verdeelde Frankrijk, deed het antisemitisme oplaaien en bracht de beïnvloedbaarheid van het gerechtelijk apparaat aan het licht.

Huis van de Europese geschiedenis, België

Strijd tegen oorlog

In een uitdrukking van onbekende herkomst wordt de waarheid beschreven als “het eerste slachtoffer van elke oorlog”. Oorlog is namelijk een uitgelezen moment voor de betrokkenen om hun toevlucht te nemen tot bedrog en misleiding. Tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog veranderde heel Europa in een slagveld, en de keuze om iemand te vertrouwen kon verstrekkende gevolgen hebben. Het duurde tientallen jaren om de feiten boven water te krijgen over de misdaden die door de totalitaire regimes waren verdoezeld en goedgepraat.

Gereedschap dat door het verzet in het Persoonlijke Identificatiekaartcentrum in Amsterdam werd gebruikt om persoonlijke documenten te vervalsen - Bezette Nederlanden, 1941-1944

Een pen, een rubberen stempel, een schrijfmachine, aceton. Moedige personen hebben met deze voorwerpen tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog duizenden levens gered. In heel Europa konden de nazibezetters met hun zeer nauwgezette administratie miljoenen Joden en andere ongewenste personen identificeren, deporteren en uitroeien. Een nieuwe identiteit kon betekenen dat je niet op transport werd gezet naar een concentratiekamp. Vervalste documenten maakten gewaagde handelingen als sabotage en spionage mogelijk. Met de juiste papieren was het mogelijk de grens over te gaan, en een vervalste rantsoenkaart kon iemand redden van de hongerdood.

© Verzetsmuseum, Amsterdam

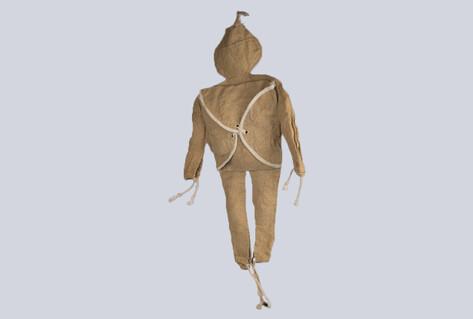

Paradummy die werd ingezet tijdens de bevrijding van Nederland, 1945

Nepparachutisten (“paradummy’s”) werden voor het eerst efficiënt ingezet door de Duitse troepen die België en Nederland in 1940 bezetten, om de aandacht af te leiden van plekken waar echte soldaten werden gedropt. De paradummy’s waren zo ontworpen dat ze zichzelf vernietigden, en er zijn er dan ook maar weinig bewaard gebleven.

Fries Verzetsmuseum, Nederland, © Collectie Stichting Verzetsmuseum Fryslân

Namaak en rijkdom

Winst is altijd een van de belangrijkste drijfveren geweest om namaakproducten te vervaardigen. Kunstwerken, luxeproducten, dagelijkse consumptiegoederen en valuta worden nagemaakt voor financieel gewin. Namaken wat mensen het liefste willen hebben, of het nu gaat om een schilderij van een Hollandse meester of een tas van Louis Vuitton, is een cruciaal onderdeel geworden van de geglobaliseerde consumptiemaatschappij waarin we leven. Namaak is echter ook gebruikt om onze onverzadigbare behoefte aan “meer, goedkoper en nieuwer” bloot te leggen, zoals in de documentaire Czech Dream over het gelijknamige experiment.

Han van Meegeren, Christus en de overspelige vrouw, Nederland, ca. 1942

Hermann Göring betaalde 1 650 000 gulden voor dit werk, in de veronderstelling dat hij een schilderij van Johannes Vermeer kocht. Han van Meegeren verdiende miljoenen door zijn eigen schilderijen te verkopen als werken van Hollandse meesters. Hij wist zowel kunstkenners als naziverzamelaars om de tuin te leiden. Toen hij na de oorlog beschuldigd dreigde te worden van collaboratie, bekende hij het minder zware misdrijf vervalsing. Van verrader werd hij plotseling een nationale held, de man die Göring had weten op te lichten. Misschien was het creëren van dit positieve imago bij het publiek wel zijn laatste grote truc!

© Museum de Fundatie, Nederland

Traditionele slof met nagemaakte Burberryruit

Vervalsers hebben zonder scrupules geprofiteerd van de hypocrisie van consumenten om altijd meer, goedkopere en nieuwere producten te willen, en tegelijk op zoek te zijn naar status, uniekheid en authenticiteit. Maar hoe meer namaak er aan het licht komt, des te populairder het lijkt te worden! Aansluitend bij de trend van “ironisch koopgedrag” wordt zelfs de voorkeur gegeven aan nep boven echt als een manier om in opstand te komen tegen het kapitalisme. Deze trend werd nog verder doorgevoerd in de vorm van gewetensvolle namaakproducten: nepbont, synthetische diamanten en veganistisch leer.

© Musée de la Contrefaçon, Paris

Het ‘niet-vervalsbare’ bankbiljet door Roger Pfund - Genève, 2012

‘Het op één na oudste beroep ter wereld’, het vervalsen van geld, is net zo oud als geld zelf. In de oudheid bestond vervalsing meestal uit het verdunnen van de hoeveelheid edelmetaal in een munt met onedele metalen en deze vervolgens te bedekken met een dun laagje goud of zilver. Maar naarmate de munt- en druktechnologieën verbeterden, verbeterden ook de vaardigheden van de vervalsers. Sinds de opkomst van bankbiljetten worden er steeds hogere eisen gesteld aan de artistieke en technische vaardigheden van zowel ontwerpers van geld als vervalsers, die elkaar proberen te slim af te zijn.

De lange geschiedenis van valsemunterij gaat hand in hand met die van ingenieus ontwerp en geavanceerde wetenschap. Dit bankbiljet is momenteel de beste poging tot ‘onvalsbaar’ geld. Het combineert de meest geavanceerde veiligheidselementen die momenteel beschikbaar zijn - veiligheidsinkt, diffractieve strip, SPARK-zeefdruk, transparant polymeer substraat - met de uitgebreide grafische ontwerpen van Roger Pfund.

© Numiservices Collection, Zwitserland

Het tijdperk van de post-truth?

De term “post-truth”-maatschappij beschrijft een cultuur waarin de publieke opinie niet wordt gevormd door feiten, maar door emoties en persoonlijke overtuigingen. “Nepnieuws” wordt vaak gezien als het belangrijkste kenmerk van zo’n maatschappij.

Toch is nepnieuws geen nieuw fenomeen. Het bijzondere van de huidige situatie is dat moderne communicatiemiddelen en vooral internet ervoor zorgen dat nepnieuws snel over de hele wereld wordt verspreid. Wanneer we worden geconfronteerd met een overvloed aan informatie uit talloze bronnen, is het vaak moeilijk te bepalen wat waar is en welke bronnen betrouwbaar zijn.

Gelukkig zijn er manieren om hiermee om te gaan: met een kritische geest kunnen we feit van fictie onderscheiden door eerste indrukken in twijfel te trekken, ons bewust te zijn van onze eigen vooroordelen en te bepalen hoe geloofwaardig de bron is. Zo leren we onze weg te banen door de complexe realiteit.

Covid-19: een infodemie

Zoals de Wereldgezondheidsorganisatie verklaarde: "De uitbraak van 2019-nCoV en de reactie daarop gingen gepaard met een enorme ‘infodemie’ – een overvloed aan informatie, waarvan sommige juist en andere onjuist, waardoor het voor mensen moeilijk is om betrouwbare bronnen en betrouwbare richtlijnen te vinden wanneer ze die nodig hebben. Maar wat is een ‘infodemie’ en hoe verhoudt deze zich tot de Covid-19-pandemie?

In dit interview bespreekt Alexandre Alaphilippe van EU DisinfoLab informatieasymmetrie, desinformatie en complottheorieën in verband met de uitbraak van het coronavirus. Hij schetst de gevolgen voor de samenleving en de media, en de maatregelen die mensen kunnen nemen om de verspreiding van de infodemie tegen te gaan.

“In onze bubbels”

Sociale mediaplatforms zijn geweldig om mensen met elkaar in contact te brengen, maar ze dragen ook bij aan het ontstaan van zogenaamde ‘filterbubbels’. Ze selecteren informatie en stellen ons bloot aan dingen die we in het verleden al hebben goedgekeurd en leuk gevonden. Deze filters wekken de illusie dat we het volledige plaatje zien, terwijl we in werkelijkheid beperkt blijven tot een beperkte mediaomgeving die we delen met voornamelijk gelijkgestemden. Aangezien dergelijke bubbels weinig ruimte laten voor afwijkende meningen en alternatieve bronnen, vormen ze een vruchtbare voedingsbodem voor de verspreiding en groei van onwaarheden.

© Huis van de Europese geschiedenis, Brussel, België

Nepindringers

Kijk of je desinformatie kunt herkennen. In dit interactieve deel van onze tentoonstelling kun je met het bedieningspaneel sociale media- en nieuwsberichten met misleidende informatie neerschieten voordat ze de onderkant van het scherm bereiken. Laat betrouwbare nieuwsberichten door of schiet deze neer met groene kogels. Door foto's, titels en bijschriften zorgvuldig te bestuderen, kun je feit van fictie onderscheiden.

© Huis van de Europese geschiedenis, Brussel, België

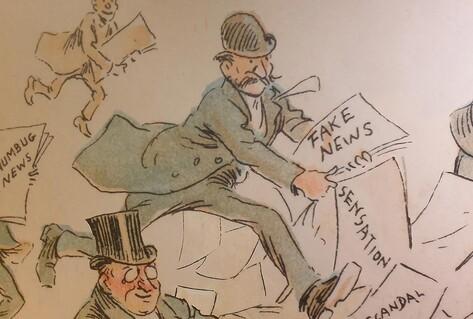

Illustratie uit ‘Puck’ door Frederick Burr Opper

Verslaggevers haasten zich met allerlei verhalen, waarvan sommige worden omschreven als ‘nepnieuws’. De term verscheen voor het eerst in de Amerikaanse pers aan het einde van de 19e eeuw.

© Library of Congress, 1894, New York, Verenigde Staten