En vous promenant dans la Maison de l'histoire européenne dans l'après-midi du samedi 27 octobre, vous auriez pu entendre une chanson folklorique estonienne jouée dans les galeries du XIXe siècle, et voir des visiteurs brandir une immense banderole en langue romani dans la section de l'exposition consacrée à la diversité linguistique de l'Europe. Tel est le résultat créatif de la décision de confier l'interprétation d'un récit soigneusement conçu sur l'histoire européenne aux voix uniques d'artistes et d'universitaires de toute l'Europe. Ils n'avaient découvert le musée que la veille, mais ils ont fait visiter l'exposition permanente, éclairant le récit du musée de leurs nombreuses visions et convictions sur l'Europe, ses nations, ses peuples et leur relation avec le passé.

La Maison de l'histoire européenne a organisé ces visites "carte blanche" dans le cadre de la conférence de BOZAR intitulée "La révolution n'est pas une garden party", organisée à l'occasion de la commémoration des 30 ans de 1989.

"C'est une situation très productive que de répondre rapidement à une exposition de cette manière (...)", a déclaré l'un des guides invités. "Le musée couvre tellement d'histoire et de questions pertinentes qu'il y a tellement de chemins possibles à emprunter. Et en même temps, a déclaré un autre invité, "il manque encore tellement de perspectives", qui doivent entrer en ligne de compte d'une manière ou d'une autre, si le musée veut être à la hauteur de son ambition de favoriser une compréhension critique et complexe de l'histoire de l'Europe.

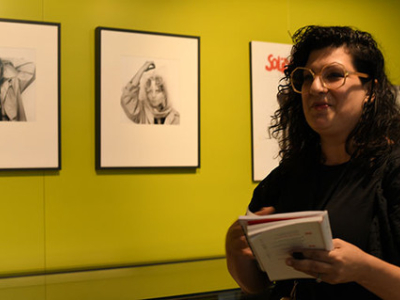

"Artivism"

Tamara Moyzes, a Prague-based multidisciplinary artist who uses the concept of “artivism” to describe her actions in the public space, found in the “Memory of the Shoah” section of the museum a story that strongly resonated with her work. A series of documents on display tell how the memory of Babi Yar, a site where 33,000 Ukrainian Jews were murdered in 1941, was intended to be erased by the ruling Communist party in the 1950s with the construction of a culture and recreation park. In 2015 Tamara, with her art group Romane Kale Panthera (Romani Black Panthers), undertook a ‘”guerilla action’” called "Happy Pork from Lety" ("Veselý vepřík z Letů") in an attempt to draw public attention to the fact that a pig farm still stood on a Romani Holocaust memorial site in Lety by Písek. Members of the group put stickers on pork for sale at a supermarket in the Prague neighbourhood of Holešovice that read: "Produced from pigs raised over the graves of Romani Holocaust victims. Uncooked."

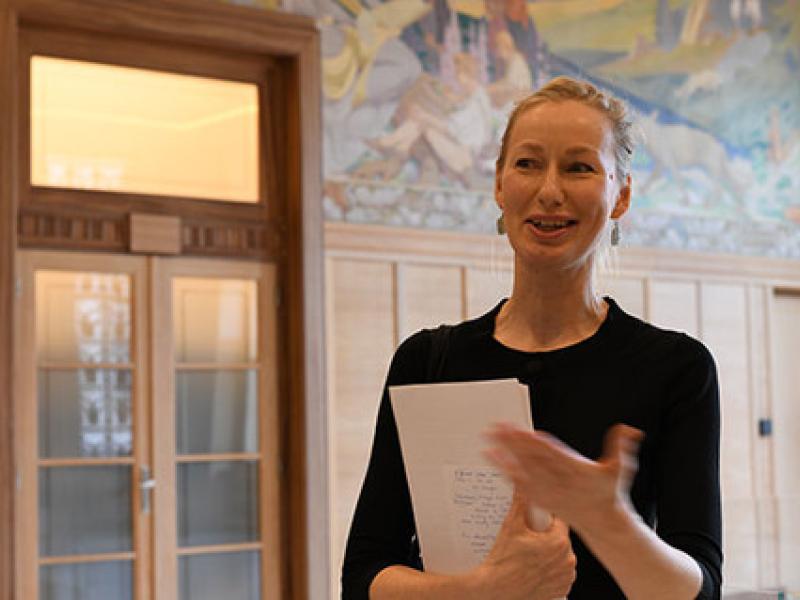

Raising national self-consciousness

Kristina Norman, whose interdisciplinary work explores the potential that contemporary art offers in dealing with the politics of memory, gave a vibrant presentation on Estonia’s role and participation in the greater European historical narrative. She presented her latest piece “Bring Back My Fire Gods” (2018), a filmed, site-specific performance carried out at the Song Festival Grounds in Tallinn, a venerated place symbolic of national liberation and the secession from the Soviet Union in 1991. The artwork exposes the means that are being used to construct a nation. Likewise, the House of European History shows how literature and language were important elements in the development of national self-consciousness in the 19th century. Kristina talked about the role Baltic Germans played in the making and spreading of the Estonian national epic poem “Kalevipoeg”, exhibited by the museum, and more largely in shaping the Estonian national identity. She argued for an understanding of every (national) culture as an ‘interculture’, and warned against the temptations of cultural exclusion every nation has, such as in the case of Estonia with the country’s vast Russian-speaking minority.

”European Union speaks Romani!”

Martin Zet, a visual and performance artist from Czech Republic, talked about languages, letters, and the meaning they give to the world we live in. He found inspiration in the museum’s Vortex of History, a 25-metre high metal installation spanning six floors in which letters of all sorts of sizes and styles swirl and twist, merging into quotations that burst into the exhibition space. In front of the exhibition’s wall of dictionaries — where one can find multiple European language combinations, and with his back to Rem Koolhaas’s huge book installation — Martin launched his ‘unstructured campaign’ called ”European Union speaks Romani!” He engaged visitors to think of the following: Why not choose Romani, a language that has never been associated with any European state system, yet is present all over Europe, as the next EU official and working language?

Maja and Reuben Fowkes, London-based art historians and curators, combined their two distinct voices in a dialogue with the House of European History’s narrative. They brilliantly highlighted how historical processes such as the Industrial Revolution or the European Integration as presented in the exhibition take on a new meaning when looked at through the prism of contemporary social concerns such as environment or gender.

Jiří Priban, a Professor of Law at Cardiff University, took his group on a fascinating journey through the greatness and misery of Europe in the 20th century, connecting ordinary experiences of people, starting with himself, with the major disruptions of the times. He showed how human atrocities and achievements exist side by side throughout history, and how culture and barbarianism are never as far apart as we would like to think. Jiří ended his tour in front of the 1989 revolutions’ video footages where he recounted his experiences as a young scholar of the great changes that were happening then.

Final thoughts on 1989

The carte blanche tours were powerful statements in dialogue with the House of European History’s narrative. They highlighted how necessary and stimulating it is to keep questioning the past and our relation to it. 30 years after the events of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe, it somehow felt like daring creativity and free thinking can still help create new political and social orders. In the words of Jiří Priban, what one could hear at the House of European History and at BOZAR during that weekend was “certainly no 1989 nostalgia but a lot of restless souls and hearts hungry for a revolution.”