En 2009, le Parlement Européen a proclamé le 23 août, la date du pacte Molotov-Ribbentrop, la Journée européenne du souvenir (appelée auparavant la Journée européenne de commémoration des victimes des régimes totalitaires). C'est ce jour-là, en 1939, un accord entre l'Allemagne nazie et l'Union soviétique a ouvert la porte à la Seconde Guerre mondiale et à toutes sortes de violences totalitaires : de la migration forcée au génocide, en passant par l'esclavage et les crimes de guerre, jusqu'à un événement sans précédent dans l'histoire mondiale : l'Holocauste.

Le 23 août ravive la mémoire de millions de victimes des régimes totalitaires, y compris les détenus des camps de concentration nazis, des camps de la mort, des goulags soviétiques et des prisons staliniennes. Notre objectif est de vous rappeler leurs histoires individuelles. L'objectif de la campagne "Se souvenir. 23 août" est de cultiver la mémoire des victimes du nazisme, du stalinisme et de toutes les autres idéologies totalitaires, que nous nous efforçons de dépeindre non pas comme un collectif anonyme, mais comme des individus avec leurs propres histoires et destins.

Film: https://youtu.be/Ncou5M6uqVw

Kazimierz Moczarski was born in Warsaw in 1907. He graduated with a degree in Law from the University of Warsaw in 1932, having undergone military service. After continuing his studies at the University’s School of Journalism, Moczarski went to Paris to study international law at the Institut des Hautes Études Internationales for two years. Later, he worked at the Ministry of Social Affairs dealing on legislation concerning working conditions.

During the German occupation, Moczarski was an active member of the Home Army, working in the Bureau of Information and Propaganda as head of the Investigation Division in the Resistance. One of the actions he organised was taking over a dozen prisoners from an armed hospital in June 1944. During the Warsaw Uprising, he was in charge of one of the four radio stations he set up himself, as well as becoming the editor of Wiadomości Powstańcze (Insurgence News - the daily newspaper of the Uprising). He was awarded the Golden Cross of Merit for his activity back then. After the total destruction of Warsaw by the Germans, Moczarski re-activated the Home Army information and propaganda centres in Cracow and Częstochowa.

In August 1945, Moczarski was arrested by the new communist authorities launching a campaign seeking to eradicate all potential opposition. In 1946, Moczarski was sentenced to ten years in jail, later reduced to five years. In 1949, at the height of Stalinism, a new round of interrogations started against Moczarski and finally he was sentenced to death in 1952. In a letter to the court, Moczarski lists 49 methods of torture used against him. His confinement with the German SS commander Jürgen Stroop during that period was one of the methods applied by his oppressors trying to break his will. In Conversations with an Executioner, Moczarski mentions Stroop’s walks, parcels from home, personal library and right to receive and send letters, all privileges denied to him. After Stalin’s death in 1953, Moczarski’s sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, but he was not informed of that for another two and a half years.

In April 1956, Moczarski was released after spending eleven years in prison and exonerated six months later. After his release, Moczarski worked as a journalist for many years. He also adroitly used the margins of available freedom to champion various social causes. In 1968, he was removed from his job when he spoke out in defence of his Jewish colleagues at the time when the Communist Party staged anti-Semitic purges.

Kazimierz Moczarski died in 1975.

The famous Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert dedicated his poem ‘Co widziałem’ (What I witnessed) to Kazimierz Moczarski. (via The Kazimierz and Zofia Moczarski Foundation)

Film: https://youtu.be/D8qlbH84ohE

Milada Horáková was born in Prague in 1901. Her father owned a pencil factory. She went to a secondary school in Prague during the First World War and then she began studies at the law faculty of Charles University, exactly three years after the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic. She graduated in 1926 and became director of the welfare department for Prague City Council. She joined the centre-left Czechoslovak National Socialist Party the same year. Since then, she was also an active member of various groups focusing on youth and women’s rights.

Once the occupation of Czechoslovakia started in 1939, Milada Horáková and her husband Bohuslav Horák joined the resistance movement and were both arrested by the Gestapo in 1940. Horáková was imprisoned in the Gestapo prisons Pankrác and Little Fortress Terezín. In 1944, she was sentenced to eight years in prison. She was subsequently sent to the Ainach concentration camp near Munich, liberated by the Allied forces in May 1945, then she promptly returned to Prague.

Horáková re-joined the National Socialist Party and became a Member of Parliament, until the communist power takeover in February 1948, when she resigned from her position. Soon, she was involved in efforts to re-establish democracy together with other former members of the National Socialist Party.

Milada Horáková was arrested by the communist secret police in September 1949, along with many other former members of non-communist political parties, and with the help of two Soviet ‘advisors’ set about preparing a case against them. Although she was forced to confess some of the alleged ‘crimes’, she tried to courageously defend herself and her co-defendants during the trial. The trial of Milada Horáková and twelve others began on 31 May 1950. It was a show trial, based on Soviet ones staged during Stalin’s purges of the 1930s. On 8 June 1950, Horáková and three of her co-defendants were sentenced to death. Despite calls for clemency from such people as Winston Churchill and Albert Einstein, the Czechoslovak president Klement Gottwald confirmed their sentences.

In the final letter to her sixteen-year-old daughter before the execution, she wrote: ‘When you realise that something is just and true, then be as resolute as to be able to die for it.’ On the morning of 27 June 1950, Milada Horáková was executed by hanging. In subsequent trials based on the same model, more than six hundred people were sentenced across the country, including ten receiving death sentences.

During the Prague Spring in 1968, she and her co-defendants were exonerated. Due to the Warsaw Pact invasion of August 1968, the exoneration process was not completed. Finally, one year after the Velvet Revolution of 1989, Milada Horáková was exonerated of the charges. In 1991, she was posthumously awarded the T. G. Masaryk Order, First Class by President Václav Havel. (via Czech Radio)

Film: https://youtu.be/OA7WBoiW1Eg

While still a child, Péter Mansfeld took part in the Hungarian revolution of 1956 in Budapest. He joined the rebel unit of János Szabó at Széna Square in Buda, one of the several strongest points of resistance of the insurgent National Guard. He acted as a messenger between various rebel units, transported leaflets as well as grenades and weapons at times, and delivered drugs from Margaret's Hospital.

Growing repression and terror by the communists in December 1956 and January 1957 led to mass executions of Hungarian insurgents and deportation to work camps and prisons. The repression also affected insurgents known to Mansfeld from Széna Square, many of whom were hanged. Shortly thereafter, Mansfeld was arrested. Mansfeld intended to free himself from prison by force, as well as to revive the revolution. He formed a group that undertook various campaigns in 1958, among others, the kidnapping and disarming of a militiaman patrolling the area of the Austrian embassy.

In February 1958, Mansfeld was arrested together with four of his comrades. Prison conditions proved to be exceptionally difficult. The boys were interrogated at night and held in small dark cells. Péter, however, retained courage and a strong spirit. The prosecutor called the boy a ‘class traitor’ and counterrevolutionary, and called for the maximum penalty.

On 21 November 1958, Mansfeld was given a life sentence. However, the People's Court in Budapest increased the sentence on 19 March 1959. The penalty was death. Péter Mansfeld was hanged on the morning of 21 March at barely the age of 18.

Film: https://youtu.be/yeeFO0Ywd1w

Mala (Mally) Zimetbaum was born in Brzesk (Poland) in 1918. At the end of the 1920s she immigrated together with her family to Antwerp (Belgium). In September 1942 she was arrested during a roundup of Jews at the central station in Antwerp. Four days later she found herself in a transport vehicle to the Auschwitz concentration camp, arriving there on 17 September. During a selection process at the entry ramp she was sent to Birkenau camp, where she received number 19880. Due to her knowledge of several languages, she was hired at the women's camp as an interpreter and messenger.

In the spring of 1940, Edward (Edek) Galiński was arrested from among a group of middle school pupils during the "AB” campaign directed at the Polish intelligentsia. On 14 June 1940, he was brought to Auschwitz in the first transport of Polish political prisoners. During the registration process he received number 531. At the camp he worked, among others, at the ironworks and in a team of builders, first in the home camp, then at Birkenau.

Edek Galiński and Mala Zimetbaum, in carrying out their duties, had relative freedom to move around the camp. They met each other at the turn of 1943 and 1944 and fell in love. Galiński initially planned to escape with his friend, Wisław Kielar. Dressed in an SS uniform he was to escort his friend to work. He even secretly received a uniform and pistol from the former Kommandoführer of the ironworks, SS-Rottenführer Edward Lubusch. However, after meeting Mala Zimetbaum he also wanted her to escape from the camp. Ultimately, Kielar withdrew from the escape plan to help the pair during their attempt.

On 24 June 1944, Galiński waited for Mala Zimetbaum in his SS uniform at their agreed-upon location. Using a blank pass for SS men that Mala stole and forged, they were able to exit outside the large guard cordon. After two weeks, however, they encountered a German patrol. The woman was detained. Galiński was able to escape because he managed to hide at the last moment. Nevertheless, he emerged from hiding and voluntarily surrendered to the Germans in order to be with his loved one.

They were sentenced to death after a lengthy and brutal investigation that failed to extract information from them about those helping them in the escape. Edward Galiński was hanged at the men's camp in Birkenau. Mala Zimetbaum slit her wrists during the execution. Afterwards, she was transported to the crematorium and probably died en route from blood loss, or was shot.

Film: https://youtu.be/aMsOzImJnz0

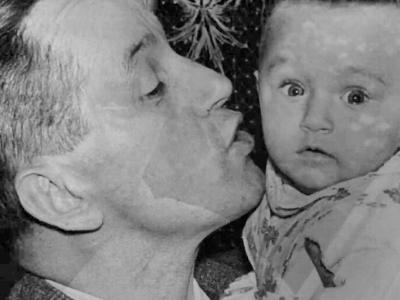

Juliana Zarchi was born in Kaunas (Lithuania) in 1938 into a family with parents of different nationalities. Her father, Lithuanian of Jewish origin, Dr Mausha (Mauša) Zarchi met his future wife, Gerta Urchs, while working in Düsseldorf (Germany). As they could not marry in the Third Reich due to racist Nazi legislation, in 1934 Gerta converted to Judaism and married Mausha in Lithuania, thus receiving a Lithuanian citizenship. Zarchis continued to live in Germany until 1937, when Mausha’s work permit was not extended. They decided to settle in Lithuania.

In 1939 the Second World War broke out. Lithuania was soon annexed by the Soviet Union, and then, when the Third Reich turned on its former ally and attacked USSR in 1941, the country was occupied by the Nazis. This is when Dr Zarchi decided to try to flee east as he assumed his Aryan-looking daughter and wife would have better chances of survival if he left. He was killed by the Einsatzgruppen, a fact of which his relatives learned only after the end of the war.

Due to her Jewish heritage, barely at the age of three, Juliana was sent to the Kaunas ghetto and forced to stay there for several months. She was smuggled out with the help of a family acquaintance, Pranas Vocelka. As her mother feared parting with her, Juliana spent almost the entire period of German occupation hidden in their house in the kitchen or in a small room next to it (only at the very end, she was taken to Carmelite sisters).

As the Soviet army re-entered Lithuania, Gerta hoped she would no longer have to fear for her daughter’s life. Instead, they were both deported to Tajikistan in Central Asia as part of a purge of ethnic Germans. They were stigmatized by the locals as ‘Fascists’ and forced to live and work in dire conditions. While the repressions eased after the death of Stalin, the exile for Juliana and Gerta only ended in the early 1960s. Juliana returned to Lithuania in 1962. She settled down and started to teach German at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas (she wanted to study medicine, but was denied the possibility due to being a deportee). Gerta joined her daughter a year later. All her life, she tried to return to Düsseldorf, but was never allowed to leave the USSR. She died in Kaunas in 1991.

Today, Juliana lives in Kaunas and is a member of the Jewish community there. She regularly travels and gives talks about her and her family’s experience of the two dictatorships.